Planning and development, green infrastructure, inland and coastal flooding and participatory engagement with Dr Mick Lennon

Dr Mick Lennon

UCD School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy

UCD Profile

Q. Your background covers geography, planning and environmental policy – what links them for you and what do you find attractive about those different disciplines?

A. That’s an interesting question and not one I’ve been asked – when I reflect on it, I wonder why – or why I haven’t asked it of myself! What interested me about geography, even in secondary school, was the interconnections between the physical and the human world. These are seen through the lens of ‘space’, and how it is then transformed into ‘place’ when you look at it from a human geography perspective. However, geography is essentially an academic discipline – although some geographers might disagree with that conclusion! I wanted something which was more change directed. In this respect, planning is more interventionist.

If I look back to my original interest in geography, melding a socio-cultural focus with the physical aspects of geography, the logical drift for me was towards human-environmental relationships. In practice this involves work at the interface between planning and environmental policy. I’m very interested in other areas of planning, such as urban design, community development and comparative planning systems. However, the relatively limited sources of research funding in Ireland means most of my time is spent researching the intersections between planning and environmental policy, even when examining issues such as urban design, community development and comparative planning systems. So, while I have a broad interest in topics across the planning discipline, this might stilt my public profile.

Q. You mention socioecological relationships as an interest of yours. Can you explain a bit more about your interest in this and why different understandings of nature matter in how landscapes, place and sociocultural relationships are produced?

A. Our existence is inherently intertwined with our environment. It’s an inescapable reality of living on planet Earth. It’s this complex interweaving of social and economic relations, of us and our environment, that I like to study. And a key dimension of this is how we conceive nature in our planning activities. So, for instance if you take something like ‘rewilding’; it’s a contested concept, both in terms of what it means and the acceptability of different approaches to what’s being advocated. From this perspective you begin to see why it’s important to look at what these concepts mean to different groups, who has power to define such concepts and ensure the implementation of their definition. Furthermore, policy is inherently normative and nature conservation is a value driven activity. So while some use the apparent objectivity of scientific methods as a crutch to support the legitimacy of their position, it is important not to lose sight of the fact the decision to propose, fund and execute ‘evidenced-based’ policy is grounded on an intersubjectively held value-based foundation. Failure to acknowledge this can lead to loose ends, dead ends and talking across rather than to each other.

“Flooding and erosion are major risks, maybe not the major risks in terms of environmental change, but they are certainly among the risks most likely to generate significant disruption.”

The Forty Foot, Dublin

Photo by Conor Luddy on Unsplash

Q. Your work on coasts has tended to be around erosion and flooding. Would you say these are some of the major risks in Ireland in terms of climate and environmental change? How much of a risk is it and what do you see as some of the ways to manage this?

A. This is actually a recent enough turn in my research. I’m looking at inland flooding too, so it’s not all about the coast. With both the coast and inland, we’ve been looking at is how many of the costs and risks associated with flooding in these places are consequent on and require solutions from planning. In this sense, our governance systems have created and embedded a lot of the vulnerabilities that influence the emergence of different types of risks in different locations. Yes, flooding and erosion are major risks, maybe not the major risks in terms of environmental change, but they are certainly among the risks most likely to generate significant disruption. In this sense I think it’s important to remember that the risks and who is vulnerable are different in different places, it’s not evenly distributed.

Contentious questions here are ‘do we need to start considering a managed retreat from flood prone areas?’ ‘How could we plan for that?’ Who will be the winners and losers?’ ‘How can policy support be obtained?’ and ‘what level of community understanding is necessary to make such a policy approach feasible?’ In failing to properly consider such thorny issues we risk repeating the mistakes of the past of parachuting well-meaning STEM experts into an area to present ‘the’ solution to a place’s ills. Yet, without the ability to get buy-in from the locality through a deeper appreciation of what’s being proposed, or why the landscape may need to change in this particular location, you are very likely to get a lot of pushback and the policy may suffer a political death. This in many cases signals the perpetuance of business as usual and a proverbial kicking of the can down the road – or in this case, down to the next generation.

Q. You use the language of green infrastructure in the context of what you refer to as the landscape perspective. Is green infrastructure the same as nature-based solutions?

A. They are associated but not necessarily the same. For example, if you had an ecologist and someone who is promoting active mobility, both could be speaking about green infrastructure but both could have very different perspectives on it. With nature-based solutions it’s kind of clearer as the natural dimension is front and centre, you know, to rewet a bog to create carbon sequestration and provide habitat. Nevertheless, bog rewetting would also be termed green infrastructure in certain quarters. It’s a complicated debate of splitters and lumpers where some seek differentiation and others consider the terms interchangeable. Policy has becoming confused and confusing on this matter, with for example the EU maintaining a firmly focused ecologically perspective on both nature-based solutions and green infrastructure, but many national, regional and local interpretations adopting a more inclusive approach. Green infrastructure is more commonly used in planning. A key aspect here is multifunctionality. In such policy discourses, green infrastructure has got a strong spatial dimension and is generally folded into planning and design activities. Increasingly, the debates around green infrastructure are also focusing on urban spaces to the neglect of rural applications.

“Elements identified as in some way providing added value to society become assets like roads, bridges and pipes – they become green ‘infrastructure’.”

Photo by Devin McGloin on Unsplash

Q. So it generally refers to something that has been planned or designed?

A. Well that depends. Going back to this issue with nature and how people interpret things differently, some people would consider a river and its banks to be green infrastructure because it’s managing water and providing habitat. Basically it’s something that has a strong natural dimension and is essential to the functioning of society. So in this sense, elements identified as in some way providing added value to society become assets like roads, bridges and pipes – they become green ‘infrastructure’. It’s a way of increasing the profile and the level of priority given to these within a system of decision making. So if you think of it as ‘infrastructure’, then yes it is something that has been – or at least can be – planned or designed. We’re returning now to our discussion about who has the power to define and implement concepts. If you have the power to define the concept of green infrastructure as that which is analogous to conventional grey infrastructure, then of course it is something that can be planned and designed. However, if you begin to unpack this logic it is only a short hop to a fungible understanding of nature than can be easily substituted when it is expedient to do so. You see, concepts do work, so they need to be handled carefully.

“Navigating competing demands is always a challenge and will likely always be a challenge, because those demands are changing, the understanding of sustainability is changing, the context is always different. So it’s not a simple algorithm that you can apply to every space like a template.”

Q. How does planning relate to development more broadly and how do planners navigate competing demands? Do you think they are often in sync or in conflict, from your perspective as a planner?

A. I used to be a practicing planner before I returned to academia and can attest that it can be a real challenge navigating competing demands, especially as firstly, what the competing demands are continuously evolve and alter in terms of their perceived importance. Secondly, the concept of what constitutes good planning is constantly changing. Planners normally negotiate competing demands through the application of policy. This may seem straightforward but there may be competing policy agendas at different scales of governance and between different policy documents. For example, how to apply policy in a situation where competing policy guidance obscures clarity of direction can result in the familiar instance where the interpretation of policy in a County Development Plan by a local authority planner is overturned by the interpretation of that same policy by an inspector in our appeals board, an Bord Pleanála.

We have instituted in our system is a series of checks that are supposed to create a sense of clarity and coherence. But it’s an imperfect system and policy often lags behind those issues which are being encountered in practice. Navigating competing demands is always a challenge and will likely always be a challenge, because those demands are changing, the understanding of sustainability is changing, the context is always different. So it’s not a simple algorithm that you can apply to every space like a template. Cookie cutter planning is rarely a feasible option!

One way of considering this is that there are three legs to the stool of planning which allow it to stand up. The first of these is development management. That’s basically about the assessment of a planning application against current policy and enforcement proceedings against unpermitted development. Another leg is policy formulation. The third leg of this stool is initiative implementation. It is through working with each of these legs that planning navigates the competing demands of development and sustainable development. If you take away any of those legs, like a stool, it doesn’t work properly.

“The planner doesn’t simply decide of their own volition as what is the right thing to do. Rather, they must base their decision on policy. They are restricted by what adopted policy is in place.”

Q. Within the process, who is most likely to advocate for the environmental considerations in a development?

A. It depends. If the environmental considerations you refer to are unambiguously defined in adopted policy, then the planner has a clear role. But it’s rarely so simple. Normally, the planners job is to adjudicate between a variety of different opinions in a way that advances adopted policy. For example, consider the case of a proposed housing development near a protected habitat. We’ll leave aside EU designated sites to simplify matters and imagine that the habitat is designated as protected under local policy. We’re currently in a housing crisis, so it’s not hard to imagine that there’s also a policy promoting housing development in the locality. An environmental assessment suggests that if the housing development is built, there is a high probability of ecological disturbance – to the brent geese feeding in that habitat or something like that. The local birders are up in arms, but so is the local homeless alliance. The planner has to weigh up these competing demands. Where appropriate they may engage with the applicant about mitigation, attach mitigating conditions to a decision to grant permission or refuse permission. The planner doesn’t simply decide of their own volition as what is the right thing to do. Rather, they must base their decision on policy. They are restricted by what adopted policy is in place. But as mentioned earlier, there is a certain degree of interpretation at play here, such that their interpretation can be questioned and overturned on appeal.

Q. So it is meant to be an objective process?

A. Yes, difficult enough as it is. If you take something like the example of the proposed housing scheme adjacent to a habitat we just discussed. There are policies and procedures in place. Often these are driven by European law requiring all forms of environmental assessments. If it’s protected under national legislation but not European, it’s slightly different again. European protected habitats enjoy a much stronger level of protection.

Q. Do you think we have a good planning system in Ireland from a planning perspective?

A. I’ll probably give a slightly different answer to what you might normally receive from our colleagues in the Earth Institute. I think it’s not great but not quite as bad as many would claim. I’m certainly not an apologist for the Irish planning system from an environmental perspective. It has its problems but all planning systems, like all legal systems or versions of democracy, have their comparative benefits and constraints. However, I would fear about the state of the Irish environment had we not the collective interest of the European Union forcing our hand on certain issues.

Q. Tell us a bit about your recent book, Planning for the Common Good. It sounds quite philosophical!

A. Yes, it’s got quite a philosophical bent to it. The basic thread of my argument is that planning in modern western liberal democracies is predicated on the ability to do good. It is an endeavour focused on processes of decision making aimed at rendering the world a better place, or at least to do no worse. In essence, the ongoing search for how to achieve this is the good of planning – it is what legitimises planning as an activity. This is rendered a ‘common’ good by the emphasis on the necessity of societal benefit that in some way must accrue from it. The book argues that there’s no objective common good to be found. Instead, it is formulated through the constant engagement with emerging challenges that require answers from planning. So that brings us back to your question about navigating competing demands. What my book discusses is the philosophical dimensions of trying to navigate such competing demands.

“Managing voices in the process is a challenge. If you’re doing co-design you’ve got to be careful that it’s not just the usual suspects that turn up, or that those who shout the loudest get heard.”

Q. You use a lot of participatory methodologies in your work, such as codesign and coproduction. What are some of the challenges and benefits or working like this?

A. Firstly some challenges. Managing voices in the process is a challenge. If you’re doing co-design you’ve got to be careful that it’s not just the usual suspects that turn up, or that those who shout the loudest get heard. It’s important to reach the quieter voices who might have more to say, or interesting perspectives that can be really insightful. That’s one issue, when working on the ground with it.

The other is a different one. Doing co-design or co-production in a way that is meaningful can be a challenge in the current funding environment. I say that because I’ve noticed that a lot of funders like the idea of co-design or co-production in proposals, but have a superficially conceived notion of what it entails. Consequently co-design is frequently viewed as something tagged onto a research project rather than centred within the research process. For co-design to work effectively it needs to be something meaningful to collaborators – a solution to something that matters to them and not just a vacuous exercise in box-ticking participation or trendy dissemination.

From the benefits perspective, obviously the one you hear a lot about is the sense of ownership by the collaborators around the process and the solutions that are co-produced. Greater buy-in means greater probability of effecting real and durable change, so that’s very important. A well thought through co-design exercise should also demystify the decision-making process. It shouldn’t be this scary decision that somebody else has produced in a way that’s opaque. Rather collaborators understand how they got from A to B to C to D, and recall how they were involved in deciding the path followed.

There’s also benefits from an academic perspective. You can often get a rich dataset for co-design. If you can record it right, it can be more nuanced than what’s achievable by other qualitative means like interviewing or focus groups. This is because when people are not actually engaged with the materiality of producing something, they may be inclined to provide answers that they think are what they should be giving, or what they think you might want to hear. But when you’re in the thick of it, when you’re debating, and rethinking and redesigning in an iterative process, sometimes the reality of what you’re doing comes to the fore a bit more and you see the issues with it and the possible ways of negotiating those.

Q. Have you worked on any projects recently using this approach?

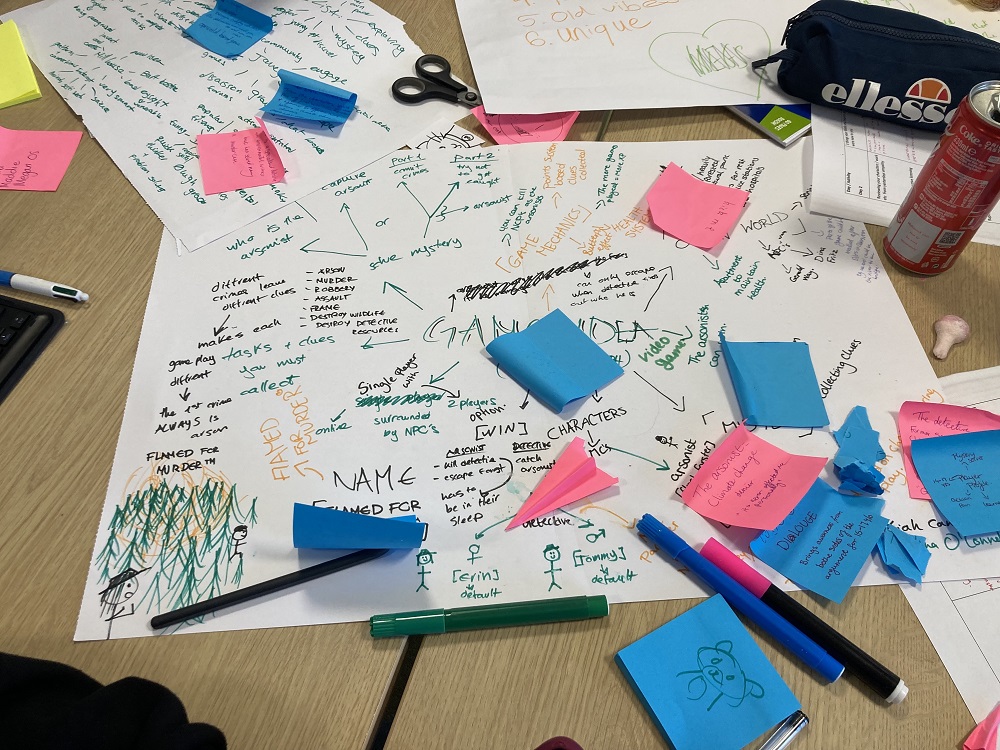

A. I’ve been working on one in the last few weeks down in Cahersiveen with Anita McKeown and Bec White from Smart Labs and some colleagues from the Earth Institute. It’s an IRC funded project called Climate Change Engage. We’re developing a framework for enhancing climate change knowledge and the sense of agency of transition year students (15-16 year olds). So we’re focused on knowledge acquisition and managing the anxiety that knowledge about climate change can bring. These students come across climate change in school but sometimes it’s very scientific, they are either terrified of it or don’t engage with it. They don’t really have a rounded knowledge on it. What we’ve done with them recently is a five day design sprint. We worked with them every day for five days, 9am-5pm. It’s a mixed group of boys and girls. We iteratively developed a framework for designing a climate change game for other transition year students in Ireland.

Most of them went for some kind of digital game but in order to do that they had to create the narrative, get the information, learn how to empathise with different types of users and so on. It’s an ongoing process. Essentially it’s developed by students, it’s students talking to students. It’s not just the science of climate change, it’s beyond that. We hope to develop a pack of lesson plans for transition year teachers, potentially those teaching geography. So there you have it, back to your first question and my roots in geography!