The role of design in urban and rural development, cultural representations of landscape, land use and land use change in Ireland with Dr Karen Foley, School of Architecture, Planning & Environmental Policy.

Dr Karen Foley

UCD School of Architecture, Planning & Environmental Policy

UCD Profile

Q: Tell us a bit about your career path and how you came to work in landscape architecture

A. I’m an accidental academic. I was a practicing landscape architect for many years, it’s something I always wanted to be. I discovered the profession when I was fourteen years old. While on a family camping holiday in Portugal I came across a book called New Lives New Landscapes by Nan Fairbrother. I followed this pursuit working as a landscape architect in a multidisciplinary design office in the UK. An opportunity to teach Urban Horticulture in the Humboldt University of Berlin Germany arose while I was practicing which I really enjoyed. Later a job came up in UCD, so I ended up back in Ireland

Q. Were there courses in Ireland when you trained?

A. No, there no landscape architecture in Ireland then so I studied abroad, in England and then Denmark. Then I came back to help set up an undergraduate course in Ireland, which was a nice thing to do.

Q: Has the field changed and developed in Ireland over that time?

A. It has definitely changed in Ireland both in terms of the growth in numbers of landscape architects in practice to the nature of the scope of the work they are now undertaking. This was evident at the recent Irish Landscape Institute 30 year anniversary event.

Q. How would you define landscape architecture as a discipline or profession, compared to planning for instance?

A. Landscape architecture is the planning, design, management, and care of the built and natural environments. At its heart It deals with land and all the processes that affect the land. This is perhaps in contrast to architecture which often, but not always, deals with an object. In landscape architecture we are dealing with the space and the natural systems that change that space, and working with those processes.

Compared to planning – we are both trying to lead towards or direct future change. However, I think a lot of planning may be a little more two-dimensional, working on two-dimensional plans. In landscape architecture, because we are very much at the intersection of science, art, design and humanities, we try to visualise what places will look like and how they will change. That’s one of the things in our repertoire, being able to envisage and communicate the spatial qualities of these proposed new designs.

Q. What influenced the growth of the field in Ireland, do you think?

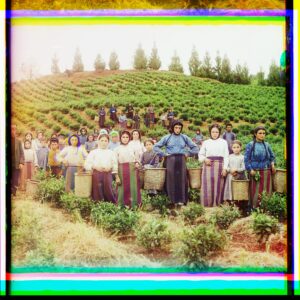

A. A group of Irish architects in the 1960s, most of whom had studied in what was then DIT Bolton Street, went off and did a post graduate course in the US, studying under regional planner and landscape architect Ian McHarg, author of Design with Nature. They came back and brought some of those ideas back into Ireland. As built development has continued, the need for landscape architecture is much more recognised now. Much of this was led by EU requirements. Today hardly a scheme goes ahead without input from a landscape architect.

“Landscape is really a social construct. It exists in the minds of people. It’s an area perceived by people. While land is often owned by individuals, landscape is a public good.”

Q. Can you tell us a bit about the role of landscape architecture within housing development and the built environment?

A. It’s an interesting question and I found this a little difficult to answer. Landscape is really a social construct. It exists in the minds of people. It’s an area perceived by people. While land is often owned by individuals, landscape is a public good. I think good planning and good design are a part of the solution to the housing crises. Starting with the masterplanning and making sure that wherever residential areas are zoned they are not areas of significant environmental sensitivity.

Landscape architects also play a role in the design of the open space in the residential design. It’s about making sure that the proposals are adapted or suitable to the Irish context, and by that I mean things like light levels. Ireland’s position in the northern hemisphere means we have relatively low sun angles. High rise buildings can cause shadows and negative microclimatic effects.

Then of course it is the quality of the open space, moving from the private open space what we traditionally call gardens – whether we still have those in the future – to the public realm, to ensure they are well designed so that people can easily access them and use them safely.

Those are key areas where the landscape architecture profession can have an input to housing, i.e. creating safe comfortable and accessible hierarchy of open space.

“Public open space in urban areas has been recognised as important, ever since urbanisation, for community well-being.”

Q. How do see the role of public space and green space in cities and why is it important to design it properly?

A. It’s absolutely crucial. Public open space in urban areas has been recognised as important, ever since urbanisation, for community well-being. I suppose before the pandemic we were talking a lot about well-being, mental health, reducing obesity, but since the pandemic it’s become even more crucial for the resilience of cities in terms of climate adaptation.

It’s about having areas to get out into, but also one of the big challenges now is getting people back into the city centre because people are working from home. One aspect driving that is the quality of the public realm. More than ever, the quality of the open spaces in cities. That’s not even touching on biodiversity and other issues, or storm water attenuation, all the other big challenges that we are facing in our urban areas.

If you just take the people aspect, it’s more important than ever to have that access to these spaces. The living space that people have to go back to is getting smaller, so the outdoor space is ever increasing in its importance, it has to be well designed.

Q. Is Dublin moving in the right direction in this regard?

A. Well Dublin has four different authorities and I think there is innovation shown by most of them in things that they are doing. In their policy documents they make reference to Nature Based Solutions and propose actions aimed at the sustainable management and use of natural features and processes. I have worked with two of the local authorities on research projects that come under the umbrella of the Earth Institute. That’s a great relationship to have.

“Nature-Based Solutions, in some ways, is just a somewhat new term for sustainable management and use of natural features and processes. It is what landscape architecture is all about.”

Q. Alongside green space we hear a lot of talk about green infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions, what can these offer us?

A. Nature-Based Solutions, in some ways, is just a somewhat new term for sustainable management and use of natural features and processes. It is what landscape architecture is all about. We deal with earth, plants, water, the natural systems, it’s just about adapting them to the urban areas. Green rooves are often mentioned, they can provide a site for biodiversity, reduce flooding by slowing down the water.

Green walls can provide biodiversity and green space. You’ve also got bioswales – traditionally water would be quickly removed off site and into sewers underground, now it’s slowed down at the surface. It seems likely that the biggest challenge we are going to face in relation to climate change in Ireland is increasing periods of heavy rainfall. These are new things that are coming along to deal with challenges in the urban environment, replacing or supplementing grey infrastructure – traditional infrastructure – with green infrastructure.

Q. What are the biggest environmental or climate challenges that landscape architecture can help to address?

Well, it’s about recognising to the kinds of predicted challenges, like increased rainfall, that I’ve just mentioned. Some of our planting schemes are very long term, you might be putting in trees that you hope will be there in – if it’s a campus situation, UCD campus for instance – you’re hoping it’ll be here in 100 years’ time. Certain vegetation can adapt, we can adapt. But if you have a sudden inundation of water, that is an immediate situation that needs an answer, so I think that will be part of it. I think we are lucky that Dublin has not had a huge catastrophic rainfall event, to date.

“We also often forget how unique we are in Ireland. We have had depopulation in the middle of the 19th century, associated with the famine, so we’ve had less pressure on the land because population growth is the biggest driver of landscape change”

Q. What kinds of particular challenges come up in terms of land use in your field, both historically and present day?

A. I think this all relates to landscape change and people. What landscape means to people in a way which they can’t often articulate, It is about sense of place; which kind of means that their home and identity is tied up in it.

We also often forget how unique we are in Ireland. We have had depopulation in the middle of the 19th century, associated with the famine, so we’ve had less pressure on the land because population growth is the biggest driver of landscape change. Therefore we’ve had a relatively stable rural landscape. The appearance of the landscape, in many parts of the countryside has not changed dramatically. Many of our hedgerows that you will see in the mid 19th century maps are still present today. Not all of them, but in many parts of the country.

Because of this, you’ve got a landscape that in many ways is fairly similar to what it looked like 100 years ago. This is in great contrast to our European neighbours and the great changes they’ve experienced, for instance the loss of hedgerows in southern England and so on. Even though we have lost trees through disease, elm and so on, we still have had this sort of unchanging landscape and it’s now going to change.

There is no way we can now meet our climate targets without change. Even asking something like, what is our rural landscape? It’s a landscape of fields, of grass and hedgerows. We know that the national herd is probably going to have to be reduced to meet our targets, this is the big elephant in the room. As we transition towards that more carbon neutral landscape, we are going from having the evidence of our energy requirements sort of hidden in the ground and extracted and used in our cities, but it’s going to become above ground, so we’ll have our wind turbines and our solar farms.

We won’t need our hedge boundaries then, because the solar farms aren’t going to walk away the way the sheep will. That will radically change our landscape. I think there will be a dramatic change and I think these changes will be driven by the challenge of livestock and meeting our Climate Action Plan targets.

“The Wild Atlantic Way is really clever, marketing something magical and untamed to an international audience. Of course historically, the western seaboard was in many ways considered to be the heart and the true landscape of Irish nationalism.”

Q. How does cultural representation or construction of landscape play into this?

A. Landscape is a social construct and, over time, attitudes towards landscape change. For instance, historically sentiments towards our bogs have changed. The colonial mindset was to exploit the land resource and bogs were regarded as “waste” land. The only valued land was productive land. That has profoundly altered.

Sentiment about the west coast of Ireland is interesting. The Wild Atlantic Way is really clever, marketing something magical and untamed to an international audience. Of course historically, the western seaboard was in many ways considered to be the heart and the true landscape of Irish nationalism. It was the furthest distance from London or indeed Dublin and the Irish language was more commonly spoken there too. All these were important in the lead up to foundation of the State.

Our agriculture history is part of the national identity as well, and as we face the inevitable land use change arising from the Climate Action Plan 2023 it seems inevitable that the ordinary working agriculture landscape will alter profoundly. In the short term we will also see a proliferation of offshore windfarms in our coastal areas.

“Most of us in Ireland live close to the coast. Coastal communities are significant because they are experiencing climate change, some areas more acutely.”

Q. Tell us about the Coastal Communities Adapting Together project. Why is it urgent to work with these communities and engage in participatory ways, and how can online methods help?

A. Most of us in Ireland live close to the coast. Coastal communities are significant because they are experiencing climate change, some areas more acutely. The ones that we worked with in Wales and Ireland, the impacts of the changes they are facing are huge. You can think of coastal erosion as an obvious one but in other places, other communities are facing depopulation, because whatever was there – fishing or industry – has moved away. They are places in flux.

For CCAT we had arranged a series of participation events with the communities we identified, but then Covid struck. In a strange way it worked very well for us because we were forced to go online. We found it worked really well. I mean there is always this concern about the digital divide, younger generation being well used to it and the older not really, but I think, due to the pandemic, many people really very quickly got used to Zoom.

Another good example of bridging that technology gap is people going along to libraries with their grandchildren. The voices of the older people were being listened to, and their stories and opinions being captured, but the younger ones were helping them communicate using technology.

Outside of my own research projects, I’ve been involved in several online town hall events recently and you get a great range of people there, more than would go to an in-person meeting. The chat function is very good- many of us don’t like speaking in public but would make a comment in the chat which can be captured. I really believe that those changes in technology mean the digital divide is no longer as evident.

I feel relatively optimistic about the these tools to access voices you couldn’t get before. A lot of people are reticent, but they will speak out in the right platform

Q. Finally, You’ve been part of many multidisciplinary teams – do you like working in that way?

A. Yes I think that it’s great. It’s a fantastic way to find out what people are doing. That’s why the Earth Institute is brilliant, you find out so much. I’m interested in lots of different areas so that’s good. Thinking back to a project I was involved in in developing years ago which was interdisciplinary as well, sometimes academics are concerned because it’s hard to get their work published, but the whole word of publishing is changing as well and I think that’s no longer the case.

I think the bottom line is disciplines tend to exist in silos, and silos thinking is not going to address the problems we are now facing. Business as usual is no longer an option, so interdisciplinarity in research is necessary to try and address the enormous challenges we face.