Quantitative ecology, human-wildlife conflict, David Attenborough and science communication with Dr Adam Kane, School of Biology & Environmental Science.

Dr Adam Kane

UCD School of Biology and Environmental Science

UCD Profile

Q: My first question to open is really to tell us a little bit about your interests, and what kinds of things you’ve studied and worked on, what got you into what you do.

As far back as I can remember, I was fascinated by nature. I was one of the kids obsessed with dinosaurs. I was basically a hipster because I was into them before Jurassic Park. That came at the right time for me. In general I always loved wildlife, watching David Attenborough documentaries growing up. I wanted to be a palaeontologist, that motivated me to go to college and I did my undergrad in UCD in Science. That was a great degree because it gave you the opportunities to sample loads of different subjects in science. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to go down the geology route or the biology route. If I was studying dinosaurs, I liked the idea of treating them more as animals than the preservation and geological side of things, so there was a paleobiology aspect to it. After my degree I did a course with the Tropical Biology Association which is an organisation that takes groups of half European half African students to different field sites around the world. The one I went on to was in Uganda to a tropical forest there. It was lectures, field trips and we had to come up with our own research projects. We all just got on famously with each other. In particular there was a professor there called Ara and the two of us were just like best of mates by the end of it. He said I should get stuck into a PhD but he said, forget about the dinosaurs, you want to get into birds, which was his interest. Later I ended up going back to Africa to Swaziland, where Ara was and helped him and a student with their study tracking bats in Swaziland.

Q. You did a Master’s in Science Communication?

Yes in DCU. I’ve always loved picking up pop science books. I read Richard Dawkins quite a bit when I was younger. That course was brilliant because there wasn’t a single scientist teaching on the course. It was all from the outside, scrutinising how science works from like a journalistic perspective. I loved the philosophy of science. It was just like a totally different way of thinking to what I’d been exposed to before. And It was great because it allowed me to get stuck into looking at dinosaurs again. I just kept trying to push this agenda throughout! My thesis was on how effective dinosaurs are communicating science from the perspective of museum exhibits. I went to a museum in Denver in Colorado in the States, and the Natural History Museum in London. I put questions to the public coming out of exhibits about dinosaurs. I asked them, what are you learning about this. I was wondering, are they in the public psyche as a as kind of monster is or do people view them as animals? That was the angle I was going for. Do people just go to see them because they are amazing, because they’re big or is there something more they’re getting out of it? I got to a very obvious conclusion, because it was very much about how dinosaurs are awe inspiring. That was really the main thing people got. Despite the bits of information being dotted around the exhibit, they’re not going in for a lecture. You’re not going in to take detailed notes.

Q. Dinosaurs are really the celebrities of natural history aren’t then? What’s the appeal?

That’s it, they’re just like front and centre. They don’t seem to go away as well. We have all of these amazing animals, that come after dinosaurs going extinct, but they don’t seem to dominate museums halls as much. I think it’s because dinosaurs are a bit more alien. We don’t have anything like that now, whereas a woolly mammoth you can go, oh it’s a hairy elephant. Or a saber toothed cat is like a lion with long teeth. Whereas a tyrannosaurus is like a chicken that was the size of a bus.

Stegosaurus

Q. How did you find your PhD and postdoctoral projects?

After the master’s I started getting more into pursuing PhD projects, more general science or biology and zoology related, related to birds. Ara who I had mentioned previous had studied vultures before. I found out Andrew Jackson in Trinity College had had also studied vultures as I was mates with lots of people in Trinity at the time. Ara is very much field biology, and Andrew does the quantitative, modelling side of thing. So we devised a PhD project and I did spent three years studying vulture biology. I did some fieldwork in Swaziland, which has been renamed Eswatini, looking at their conservation, their movement, that kind of thing. I loved my PhD, I thought it was brilliant. I ended up staying for an extra year doing some teaching. I got like a teaching studentship and found that I loved teaching as well, which was a lucky coincidence.

I found a postdoc in Cork, looking at seabird biology. There are lots of analogies to be drawn between how vultures operate and how seabirds operate. Both are looking for food and this is [in a] sparsely distributed landscape. They don’t know where the food is really, and they have to rely on their senses, to find other cues. I ended up doing another postdoc with Tom Reed who is an evolutionary biologist. It was a total shift for me in terms of the modelling techniques, looking at the migration of fish, like salmon and trout. With trout, some populations will go to sea and others will stay put in the freshwater. We were trying to get an understanding of what’s driving those differences. It seems to have an energetic basis to it, you’re matching your energetic state or your quality to what the environment is like. If I’m in terrible quality, I go to sea and trying to ramp up my feeding opportunities and get large and come back and have better mating success, or I’m okay at the moment I can stay put and take my chances here, because it’s less risky than going to the ocean where you’re going to get battered, loads of predators, it’s a much more rigorous environment. I applied to lots of positions and finally landed an interview in UCD. In 2018 and last year I just got my first PhD student.

Q. What’s your PhD student working on?

I had a bit of a side project in Cork looking at the impacts of nature documentaries on public behaviour and attitudes to conservation. And I thought we could broaden this out to look at human wildlife conflict more generally. Human wildlife conflicts across the board, are often thought of a human problem. Grace Nolan is my PhD student. She had worked on this sort of stuff before, looking at conflict situations in Australia, with dingos for instance. Her project is looking at Attenborough’s more recent work where his focus has shifted to discussing the conservation topics much more explicitly. In the past he had said, oh look at nature it’s amazing. He was hoping that this would inspire people to do right by the natural world but he was criticised quite a bit for this. People said, this is not a realistic representation of what’s actually happening in nature, you need to showcase some of the disasters as well. That’s what he’s been doing since.

In the project, we were motivated to ask, is there a big deal to this? We were showing that even if he does just mention the species, and doesn’t talk about their conservation status, people still start looking for them online, search Wikipedia articles. The only thing is it doesn’t seem to translate into anything constructive, not we could measure anyway. I mean it might, but it’s just a lot more difficult to measure. Going on to Wikipedia doesn’t cost anything, donating $10 to the WWF does. I mean there is a role for that, it can’t be doom and gloom all the time, there has to be some entertainment aspects and escapism.

Q. Tell me about birds and movement ecology and your interest in this area

So first of all, birds are dinosaurs so I got there in the end! That was for sure part of it. Plus they can fly, which is incredible behaviour as well. You don’t see that very often. It’s bats, birds, insects, and the extinct pterosaurs are the groups that can fly. So that adds a totally different dimension to analysing them and how they move around in the world. One thing that I really got interested in during my PhD was how information flows between different animals. Vultures cannot kill animals themselves. They’re total reliant on carrion. So they have to wait, either for an animal to die or less commonly they can wait and hang around where a predator has killed something and they clean up the scraps. We were able to track the order of arrival of the different species to the carcass. Almost every time an eagle lands the vultures follow pretty shortly afterwards. We think the eagle represents a more conspicuous signal to the vultures than something that’s stationary on the ground, like a cow or a gazelle or a zebra or whatever it is, that isn’t moving. The eagle is sitting on top of the carcass, chewing away. Even its descent to the ground, it’s more conspicuous. Then the vultures then come down to the carcass, shoe off the eagle because, they dominate them and get the food for themselves. Subsequent research shows that the chain of information goes back even further still, jackals and hyenas will look at the birds descending, the vultures descending to the carcass, then follow in on them. There’s this kind of neat information transfer going on between the different animals in the scavenger community.

With the seabirds, I was kind of interested in similar stuff. How were they finding food? Over the ocean, the fish are below the surface, they’re not jumping up begging up to be eaten. There were two seabirds that I had worked on for the postdoc, a group called the tube noses. They have this finely attuned sense of smell. They seem to be able to zone in on areas where plankton has been broken down. Where you have plankton, you’re likely to have other animals that are higher up the food chain that the birds will prey upon. We were putting GPS tags on the birds because we can’t observe them directly. They go out hundreds of kilometres to sea. We found that they’re always slowing down and searching around the areas where there’s an increase in that chlorophyll concentration. Even though it’s remote and only picked out from the shape of the track you can match that behaviour up with satellite data which gives you the colour of the ocean and the nature of the water. This is stuff that wouldn’t have been possible a few decades ago. Even GPS tracking is pretty new technology as well for birds it’s usually limited because of the size of the tag. There’s a general rule in ecology and in movement ecology, that it can only be 3 or 4% the body mass of the bird, you don’t want to overburden.

“Vultures were absolutely hammered in Asia, because farmers were using this anti-inflammatory drug on their cattle, which they had no idea was completely lethal to the vultures. Three of the species of vultures were knocked like to critically endangered, 99% population decline, absolutely devastated.”

– Dr Adam Kane

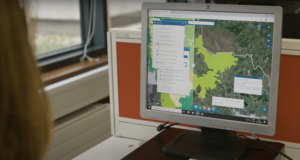

Q. Are these remote sensors really useful?

Yes, you can’t be there observing them at sea, it’s impossible. Even with other animals it’s almost impossible. It’s so labour intensive to observe an animal for a long period of time. Your mind is going to get blurred. It doesn’t matter if it’s an elephant or a chimp, in a relatively small environment, it is so tedious to have to sit there and code its behaviour for any length of time. It’s really cool when you can combine the remote sensing environmental data with the movement track as well so you can relate the animal movement to a really high-resolution understanding of what the environment is like. We can have the whole environment mapped into grid squares where we know what temperature was, the elevation, the landscape, and relate the animal movement to that.

Q. So you can get a really true picture of what’s happening?

Yes. Although I think people are pushing back a little bit against that because you do have to make sure that that grid square is accurate. Like it says rain forest and you were there and it’s a village. You need there to give some ground truth to it as well, so I think field biology will be around for a while longer.

Q. What kinds of human-wildlife conflicts can come up with vultures?

Vultures are an interesting one. They were absolutely hammered in Asia, because farmers were using this anti-inflammatory drug on their cattle, which they had no idea was completely lethal to the vultures. Three of the species of vultures were knocked like to critically endangered, 99% population decline, absolutely devastated. It happened so quickly, people basically thought it was a disease that was wiping them out like a virus, it was just unprecedented numbers. It happened because they have this kind of social behaviour when they all find and go to the same carcass, they can be knocked out really easily. In Africa there’s lots of threats, poisoning is one of them. Poachers don’t want their signals to be revealed by the circling of the vultures over the carcass so they will set out poison bait on the animal they’ve killed and knock out that whole population of birds. People kill them for lots of different reasons, for foods, for traditional medicine. As a group overall, they don’t have the best publicity.

White-backed vulture

Q. Do vultures provide a useful service by eating dead animals?

When they aren’t around, decay seems to take a lot longer. People try to experimentally set this up and things like disease potentially spread much more readily in the environment without vultures, because the animal’s just left to rot. Other animals might start interacting with each other, like the mammals will start interacting with each other much more often. So in Asia and India, I think they reported an increase in things like rabies when the vultures were wiped out, so from that that perspective they hugely important.

Gulls have a fairly similar ecology, because although they are not only scavengers they do clean up the mess, I mean they are a bit of kind of nature’s clean-up crew. You can see in town if there’s food left around, they’ll just devour it, it’s gone. It is a service that they can provide. The gull side of things came along during my postdoc and it was like linking in the kind of movement ecology with the sci-comm human wildlife conflict side of things. My hope is to try and get some funding to find out where they’re feeding in urban environments and really to see if there’s any distinction between the birds that are nesting on rooftops compared to where they forage if they are nesting in more natural locations, like on the islands just off the coast, around Dublin basically. Just a cursory kind of reading of how they are portrayed in the media is just insane. It’s like they’re just these monsters coming to snatch our puppies kind of thing.

Q. Why do you think gulls get such a bad rap?

There’s generally a couple of reasons that people are spooked by them. They can be really aggressive around the breeding season, so they will kind of dive bomb you if you near the nest. They are loud. People think they might be able to spread disease, because it seems that we spread disease to them and then they spread it around themselves. I thought it was a good analogy that dogs do all of this stuff as well, they’re loud, they can be aggressive, dogs are big enough that can kill people. A gull is never going to kill a person. What are they? A couple of kilos? People will accept risks that they’ve already allowed, you’ll go skydiving and you’ll take those risks but you don’t want to be dragged on a skydiving trip that you’re not interested in. We are not interested in wildlife breaking down our bubble of urban society and it’s like I was saying about Attenborough, it’s mad that it might be due to our lack of exposure to nature that makes us less tolerant of other species. You even see it with pigeons, you know, ‘rats with wings’. They’re just animals. It’s crazy.

“I think [rats] have an interest in their own right in being able to exist even in urban settings, when we’ve trashed their natural environment. They’ve set up a whole different ecosystem and they’re still able to kind of hang on and flourish even”

– Dr Adam Kane.

Q. The kind of language and its association is very interesting, this idea of being vermin or dirty. And that can be applied to people as well, a kind of othering.

Yes, if you spread disease, then you’re dead to us. Obviously rats do spread disease and very famously so but that’s not the only thing they do. I think they have an interest in their own right in being able to exist even in urban settings, when we’ve trashed their natural environment. They’ve set up a whole different ecosystem and they’re still able to kind of hang on and flourish even. You see it even around spiders, anything that comes into your house. It’s like this threshold that you have. There’s me, there’s the world out there, don’t come in. Even when people say that the gulls are really aggressive, they’re just trying to defend their nests. Or swans, that people think are aggressive sometimes. It’s exactly the behaviour they were selected for, that works. If you defend your young, you’re more likely to have young that survive, that can reproduce and survive to the next generation which is kind of the game that natural selection is trying to work towards.

Q. Where did you develop your interest in statistics and quantitative methods?

Andrew Jackson in Trinity really sparked my interest in stats. It is one thing that people usually shy away from. It comes back to how biology is thought of as a subject, that it’s not quantitative, so as a science subject it’s not as quantitative as physics or chemistry. So people will do it but then when you get to like university or PhD level you’ll see that every single paper has a huge amount of quant methods built into it and you’re at a complete loss if you don’t have a good understanding of these. I audited a few of his courses and did my own reading and I really got into stats. It really helped me because I ended up being able to help or just advise people, to come on as a co-author for a few projects. That really stood to me.

Q. Explain a little about conservation biology and some of the challenges in dealing with human wildlife conflict

Conservation biology is a relatively new subject. Calling it this only emerged in the late 70s, early 80s. It was called a crisis discipline so it’s kind of apart from environmental biology because something bad has already happened and it’s like oh we have to marshal our resources to help prevent these species from going into extinction. The vulture case in Asia was a pretty good example of what you’re asking about because there was this puzzle. Why are they dropping dead, what’s going on? People were coming up with put all these different hypotheses and saying oh it’s a virus, it’s climate change or habitat loss. But the number of them just disappearing was stark and they had this very diagnostic symptom. They have these really long necks, they would be kind of sagging to the side and just clearly looking sick.

Scientists did have to be brought in at that stage, to sample the carcasses of the bird and relate the levels of poison in their system to what was in the environment and show that this is something that can cause death of these birds. Then experimentally, to sacrifice a couple of poor unfortunate vultures as well and treat them with the poison, to show it kills. From one perspective there wasn’t so much of a conflict going on there, but in a scenario say like with the gulls or even in Africa with the vultures, there’s a bit of a tete a tete going on between the humans and the wildlife. Scientists can often shy away from the conservation issues when it comes to dealing with people. Because it turns into politics. It seems strange, we get all this biology training, philosophy, stats. Policy surely has to come into play if you’re a conservation biologist.

I think this is probably something that a lot of people shy away from. It’s like, I just like wildlife, I want to study this or even with Attenborough, I want to show you what the natural world looks like I don’t care about the horrible side of things. Some people would argue that we have an obligation to help protect these animals because you can’t appreciate them if they’re dead. They’re going to go the way of the dinosaurs, stuck in museums and it will be the fault of humans.

It’s a very complicated issue because conservation issues tend to be human problems. It’s people trying to extract resources for their own benefit. Even the poaching scenario. It’s people trying to make a livelihood by killing these animals and trying to sustain themselves. Even what we think of as like the worst aspects of the criminality of conservation and conflict, at the end of day they’re not I don’t think they’re going out of the way to make the animals’ lives miserable. They’re not torturing the animals, they’re just trying to sustain themselves. I think sometimes it helps to kind of come at it from the perspective of the people who are on the other side of the conflict and see what’s motivating them to do this. Sometimes that narrative that humans are the disease or humans are the virus on the planet, it’s just totally unhelpful. Again, it turns into this othering of people as well.

Q. I suppose however you feel about people’s behaviours, it doesn’t get you anywhere closer to where you want to be.

That’s it. And you know, we are animals as well. I know we have this consciousness that’s so much higher than around the ones that we know of anyway, because we are animals we still have a kind of instinct, we did evolve.

“Some have argued that because we have such a technocratic or technologically influenced society and science has such an impact on the natural world, it would be to the benefit of everyone if people understood how science works.”

– Dr Adam Kane

Q. Finally, science communication and public engagement that you mentioned at the start, what do you think the role of science communication is and also are there enough scientists during science communication?

Well, I think it helps to understand how science works but I don’t think you need to be a scientist per se. The Master’s I did like I said, to a large extent, they were journalists or philosophers. They could appreciate how the system works there and they were certainly communicating. There are lots of different roles. Some have argued that because we have such a technocratic or technologically influenced society and science has such an impact on the natural world, it would be to the benefit of everyone if people understood how science works. I do think there’s an element of truth to that, but for a lot of aspects of science. There’s quite a bit of controversy.

There is one outdated perception of how science communication works, which is like the ignorant public need to be spoon fed information by these knowledgeable scientists. it’s a very paternalistic view of how sci comm works. For subjects like biology, we’re basically pushing on an open door, because people are naturally fascinated by nature and the natural world. You don’t have to have a zoology degree to watch a David Attenborough documentary or to appreciate how the world works. I do think that people are willing to take a lot of information from scientists, because they just find it interesting in its own right, like Attenborough talking about the natural world. People think, that’s cool and they will definitely take in how big is an elephant, what’s the gestation period of a giraffe. They call it ‘gee whizz’ science.

On the other side of things, I think there’s more nuance required. For instance, if you’re trying to implement some policy for land use change, and you have agricultural lands and you’re saying that it would be good if you flanked your farm land with hedgerows or a bit of woodland because that’s going to increase the pollinators. That requires a lot more nuance I think. Because you’re not just explaining this gee whiz aspect. You’re saying there’s going to be some overall benefit that might not happen straight away. It might be down the track, there might be some tension. That’s where science communications turns into politics again. There’s a lot to be learned.

Storytelling overall is a really useful way to talk about science. Like one of the classic books, I know people don’t have a lot of time for him anymore, but Richard Dawkins, I think it was in The Ancestor’s Tale, he charted how we’re all interrelated and how we all share common ancestry with each other, all species of life on earth, but he used the Canterbury tales as a way to explain it. It was a really neat narrative. And we love stories, especially in Ireland.

David Attenborough