Prehistoric Irish foodways, present-day food security, and the Paleo Diet with Dr. Meriel McClatchie, School of Archaeology.

Meriel McClatchie

Assistant Professor

UCD School of Archaeology

UCD Profile

Ancient Food & Farming Blog

Q: What draws you to the study of past diets and agricultural patterns?

A: I come from a family who are very interested in food. When I was growing up, my mother established a bakery that supplied local delicatessens, and all the family had small jobs in the bakery. During my teenage years, I began to encounter passionate advocates like Darina Allen, who really stimulated my interest in Ireland’s food heritage. My grandparents were keen gardeners and horticulturalists, who shared their love of plants with me, and through tending my own little patch growing up, I developed an interest in plants. When I started at university, I was thrilled to learn that

I could combine my interests in both food and plants through archaeology, specifically in the area known as ‘archaeobotany’.

Archaeobotany is the study of human interactions with plants in the past. I am particularly interested in finding out what people ate and how food can provide a window on broader social phenomena. Many scholars have demonstrated how food is not only good to eat, but also good to ‘think’, encouraging us to reflect on social experience and materiality. Exploration of ‘foodways’ is an increasingly popular approach when investigating ancient foods because foodways encompass not only the foods we eat but also the social, cultural and economic practices that influence what we

choose to eat, how we consume and what we avoid. Foodways can be an expression of so many intersecting aspects of our lives, including status, ethnicity, gender, age, religion, social relations and economic circumstances. It is complex, but by taking this approach, we can start to understand the ‘meaning’ of food for people long ago.

Q: What can we learn from archaeology about the changes and continuities in the Irish diet?

A: Archaeology can provide unparalleled insights into past diets in Ireland because we can investigate the actual remains of plant foods that were eaten hundreds and thousands of years ago. During an archaeological excavation, large samples of soil from different activity areas are taken for scientific analysis, for example from house floors, pits and ditches. The samples are brought to a laboratory for processing, which enables any surviving plant materials to be recovered, such as seeds and nutshells. The plant components are preserved because they were buried in wet conditions (waterlogged) or burnt (charred), which enables fragile plant material to survive for thousands of years. With the aid of a microscope, we can identify the different types of plant remains present, and then build up a scientifically accurate picture of what people were eating in the past, at different times and in different places.

“Back in the Mesolithic period, people ate very different types of tubers, including Ranunculus ficaria or lesser celandine. Above ground, lesser celandine looks a little like buttercup, but its petals are more pointed. When you dig up this plant, you will find a cluster of small tubers. Mesolithic communities collected these tubers as food.”

– Dr Meriel McClatchie

Q: What might surprise people about what we did or didn’t eat in the past in Ireland?

A: We have good evidence for plant foods in all periods of history and prehistory. The earliest archaeological evidence for settlements in Ireland dates to the Mesolithic period, which began around 10,000 years ago. Over the following four millennia, hunter-gatherers made use of many different environments to gather, hunt and fish for food. Some of their plant foods will be familiar to us, such as nuts, fruits and leafy greens.

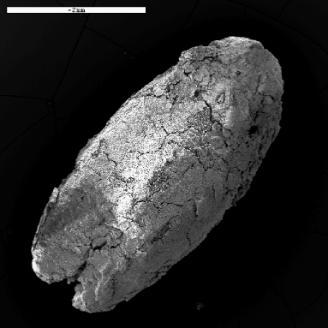

But it is less well known that Mesolithic people also ate tubers (underground stems and rhizomes). Nowadays, tubers like potatoes and carrots are strongly associated with the Irish diet. Back in the Mesolithic period, people ate very different types of tubers, including Ranunculus ficaria (lesser celandine). Above ground, lesser celandine looks a little like buttercup, but its petals are more pointed – it is in flower now around the country, so have a look for it if you are out walking within your 2km. When you dig up this plant, you will find a cluster of small tubers. Mesolithic communities collected these tubers as food.

They are tiny compared with potatoes and carrots, but they provide a starch-rich carbohydrate resource. Like many plants, they require processing before consumption – in this case they must be heated because they can be mildly toxic if consumed raw. The tubers can be cooked or roasted, and then ground to make flour, which can be used to produce biscuit-like products. We have found burnt examples of these tubers at several Mesolithic excavations in Ireland, highlighting a long-forgotten food of our ancestors.

Q: One major thing that food archaeologists study is what is known as the first agricultural revolution: when humans first began to domesticate plants and animals. What was so transformative about this in terms of human development and our relationship with the environment?

A: The transition to agriculture around the world continues to fascinate archaeologists, and the application of new scientific techniques means that this topic will remain a focus for many years to come. The advent of farming had important ecological, social and economic consequences. Preceding hunter-gatherer societies did build houses and sometimes even large monuments, managed plants and animals to some extent, and developed societies that had elements of complexity. But farming societies often did this on a very different scale; there is more extensive archaeological evidence for ‘settling down’, clearing of woodland and increasing populations. People engaged with plants and animals at a new level, which can be seen through the morphological and genetic changes brought about by the domestication of plants and animals.

In recent years, genetic studies and careful radiocarbon dating of remains has shown that there was not one ‘revolution’ or rapid transition to agriculture that spread across the world. Instead, the origins of agriculture involved protracted and entangled processes in a variety of locations. Explaining both the origins and impacts of agriculture is still one of the most complex and contentious issues in archaeology, however, and we have much more to find out.

“Explaining both the origins and impacts of agriculture is still one of the most complex and contentious issues in archaeology, however, and we have much more to find out”

– Dr Meriel McClatchie

Q: Tell us about DIVERSICROP - the value of interdisciplinarity and why ancient grains are so relevant to today’s crop science and agriculture industry?

A: DIVERSICROP is a new Earth Institute-funded project that brings together experts from four diverse Schools in UCD to tackle a major global challenge: food security. With an increasing global population, we need to sustainably produce nutritious food, within the context of changing agroclimatic conditions. Currently, only around 20 plant species make a major contribution to human dietary energy intake. DIVERSICROP has been established to tackle this issue by building an international research network, led by UCD. The network will identify underutilized crops that are suited to European climates, that were cultivated in Europe’s distant past, that are stress resilient and that have the potential to supply key nutrients and improve diets. Promotion of these crops will encourage diversification of the food chain and support agricultural sustainability and human nutrition, helping us to meet several of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

My role on the project is to identify crops that were grown in the distant past in Europe, but are not widespread nowadays, perhaps because of social avoidance (they are not seen as part of people’s modern food cultures) or perceived low yields. I am working closely with other researchers on the project who are exploring crop science, stress resilience and agronomy, nutritional value and potential contribution to diet, and how and what policies can promote adoption of crops by seed growers, farmers and consumers. This is a complex challenge, but it can be achieved because our interdisciplinary team brings together skills and knowledge from UCD’s School of Archaeology, School

of Biology and Environmental Sciences, School of Agriculture and Food Science, and School of Politics and International Relations.

In these days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are more aware than ever before of the need for sustainable food chains to supply our nutritional needs, and the important role of local production. DIVERSICROP is timely, therefore, and our PI, Dr Sónia Negrão, and the team are delighted to have been given the opportunity to pursue this through the Earth Institute Strategic Priority Support Mechanism 2019 funding scheme.

“With an increasing global population, we need to sustainably produce nutritious food, within the context of changing agroclimatic conditions”

– Dr Meriel McClatchie

Q: Is there a danger that archaeological knowledge around food loses something in translation to popular culture. For instance, do people have a somewhat fanciful take in terms of the Paleo Diet or how hunter-gatherers lived more generally?

A: It is wonderful to see the huge public interest in ancient foods that has emerged over recent years. In archaeology, we want to help the public learn about the deep history of Ireland’s food heritage by sharing our latest results from high-quality scientific investigations. Through archaeological science, we have really detailed evidence now on many aspects of people’s interactions with plants in Ireland’s past.

The challenge is to get the public to engage with our findings. Sometimes the public’s perception of ancient foods is based on outdated understandings – a good example of this is the foods of hunter-gatherer communities, who lived in Ireland for thousands of years before farming arrived. The bones of animals, fish and birds were found on many Mesolithic excavations, which led to a perception that diets were meat focused. But through improved techniques in the recovery and identification of remains, we now know that plants also played a key role in hunter-gatherer diets,

including carbohydrate-rich plants such as the tubers mentioned previously.

Our scientific evidence provides a sharp contrast with the Paleo Diet, which suggests a low-carb diet for hunter gatherers. It is important to be clear in archaeological science that there are limits to our knowledge, however. Currently, we cannot say if hunter-gatherer diets in Ireland were more focused on meat or plants; instead we know that regular use was made of both. More broadly, I would be very wary of making blanket statements about hunter-gatherer diets globally. The one thing that hunter-gatherer communities have in common is that they are extraordinarily diverse. Different people have different engagements with plants in different locations across a very long period of time.

Popular culture sometimes suggests that hunter-gatherer communities were healthier, and that since the advent of farming, we have become increasingly unhealthy. The scientific evidence simply does not support this. Modern life can be hard. Increasingly in social and political life we hear the argument that ‘things were better in the past’, without any real analysis of if this is actually true. Food studies have not been exempted from these imagined pasts, unfortunately.