Environmental humanities approaches to the culture, power and politics of water and other environmental projects in Palestine and elsewhere with Dr Hannah Boast.

Dr Hannah Boast

UCD School of English, Drama and Film

UCD Profile

Q. You just recently published a book called Hydrofictions: Water, Power and Politics in Israeli and Palestinian Literature and you’re currently working on another book about Water Crisis and World Literature. Can you tell us a bit about your career trajectory towards this?

A. Before I came to UCD I had a Leverhulme early career fellowship at Warwick University. I was teaching fellow for three years before that at Birmingham. Prior to that I did my PhD in English and Geography in York and Sheffield. It was a White Rose project. The White Rose is a university partnership network, named after the white rose, which is the symbol of Yorkshire. I was part of a network about hydropolitics and culture, with PhD students at York, Sheffield and Leeds. The other PhD students, Christine Gilmore and Will Wright, worked on the displacement of the Nubian people for the construction of the Aswan High Dam and relationships with the sea after the Sri Lankan tsunami. My project was about water in Israel and Palestine, which became the book.

My undergraduate degree is in English and Philosophy. I was always interested in Politics and Political Philosophy, and that led me to being interested in Israel and Palestine. I was also involved in green politics and I was and still am interested in the common assumption anything presented as an environmental project is automatically good. Israel’s various environmental projects are quite obvious examples of where that is complicated. The project I was first interested in was the tree planting projects in the early and mid-twentieth century by the Jewish National Fund, a Zionist land purchase and management agency, that has since rebranded as a green organisation.

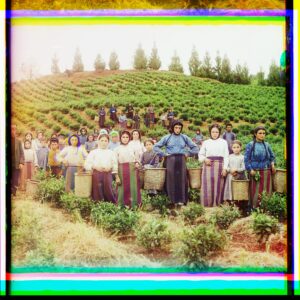

We might think that tree planting is unproblematic, but often these projects, which were usually non-native species, were not very good for the environment. It was usually pine trees, which weren’t suited to the climate and were susceptible to forest fires. They were also part of the colonialist project of occupying land and resignifying it as Israeli and European. They were often planted over the ruins of Palestinian villages after the 1948 war. I studied Israeli literature during my MA in Postcolonial Studies in York and ended up writing an essay about tree planting projects in Israel. Then that became my first article. These ambivalences around environmental projects are the basis of my research.

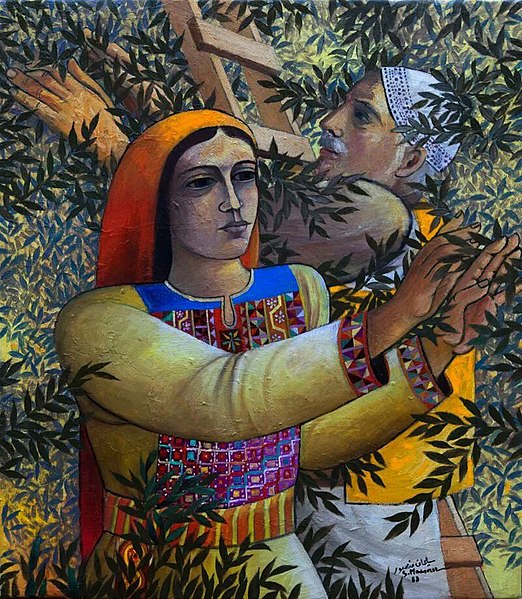

“The olive is a major agricultural crop that also signifies Palestinian peoples’ connection to the land and their rootedness which has been disrupted through their displacement.”

Image: Olive picking – Sliman Mansour

Q. What kinds of representations were there of these projects in literature?

A. There are a lot of references to trees in Israeli and Palestinian literature and art because trees are part of how we experience the environment, and because they symbolise the nation. Of course, there are reference to trees in all literatures and cultures. Think of the British oak tree, used as symbol of the persistence and stability of England. In Palestinian literature and art, including poetry by Mahmoud Darwish or Lisa Suheir Majaj, you see the olive tree, which is economically and culturally important. The olive is a major agricultural crop that also signifies Palestinian peoples’ connection to the land and their rootedness which has been disrupted through their displacement. In Israeli literature there are depictions of forests planted over Palestinian ruins. These contain histories Israel would rather forget. In Oz Shelach’s Picnic Grounds, a history professor takes his family to ‘a quiet pinewood near Giv’at Shaul, formerly known as Deir Yassin.’ This is Jerusalem Forest, part of the city’s ‘green belt’, which covers a number of former Palestinian villages, including Deir Yassin, site of a massacre of Palestinians during the 1948 War. Shelach writes that the professor ‘imagined that he and his family were having a picnic, unrelated to the village; enjoying its grounds outside history.

“I’m trying to look at literature as another form of evidence, another form of archive that we might use in looking at environmental issues.”

Q. Do you have to do a lot of contextual research to pull together lots of different types of evidence beyond the literary?

A. I see my work as a project aligned with political ecology. I’m trying to look at literature as another form of evidence, another form of archive that we might use in looking at environmental issues. This angle has often been neglected. When we think about water, we might think of it as a technical issue for engineers and scientists. We might think of water crisis and water conflict as something that can be solved through political negotiations and technical calculations. They are not necessarily things that are thought of as having a cultural component. I’m trying to think about how we might look to literature to understand the kinds of ideas and norms that govern how we manage water. In my work I explore meanings that it has for people, and how that has political effects.

“Water wars is a narrative that circulates in a political context and in the media, often in a scaremongering way. I’m interested in how literature draws on those political, scientific, media discourses, filtering and reflecting it back to us.”

Q. How can literature reveal issues like geopolitical tensions, power relations and inequalities in relation to water specifically?

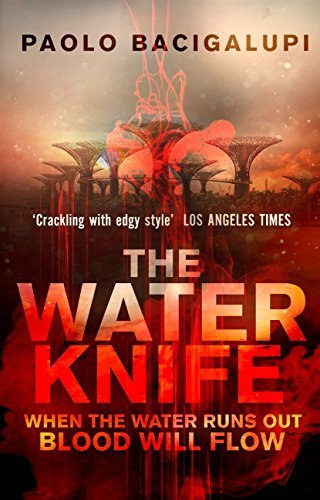

A. I’m conscious that in my earlier answer I talked lots about trees there rather than water, which is my main focus now. So one thing I’m interested in is literary trends – what themes people are writing about and what genres they are using to write about them. There have been a lot of novels recently about water wars. I’ve written an article about that a few years ago which was the beginnings of my Water Crisis in World Lliterature book. My UCD Environmental Humanities colleague Sharae Deckard has also written about water war novels. These are books like Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, Emmi Itäranta’s Memory of Water, or Assaf Gavron’s Hydromania. These are about water wars in the not-so-distant future, often just fifty years into the future.

Water wars is a narrative that circulates in a political context and in the media, often in a scaremongering way. I’m interested in how literature draws on those political, scientific, media discourses, filtering and reflecting it back to us. Literature can give us insights into political and media narratives around water, and why certain narratives persist. Yet I don’t think these water wars novels are very helpful. Often they can feel disempowering for people to read, and they reinforce pessimistic ideas about human nature where everyone is out for themselves.

The literary scholar Matthew Schneider-Mayerson has done surveys with readers of some of these books, particularly Bacigalupi’s book, The Water Knife, and he’s found that they often reinforce individualistic and reactionary views about human nature, which is not really what we want when thinking about how to live together in a climate-changed future. I think literature can reflect some of the more troubling aspects of how we talk about water but I’m also interested in how it might offer alternative ways of thinking about water, and alternative hydrosocial futures.

Q. I’ve seen you use visual materials in a presentation on your work, do you often use these in parallel with texts?

A. I’ve not written that much about visual culture and Palestine, but there are some really great resources on this. In my Earth Institute talk I used images from the Palestine Poster Project Archives which is a website that collects artworks, posters and imagery from the Palestinian, Zionist and Israeli national movements. Visual culture is a really good way to immediately show some of the ideas and narratives that also circulate in literature. I’d like to do more work on this in the future because there are more and more Palestinian artists thinking about issues of climate change and environment in their work – such as Larissa Sansour, a Palestinian filmmaker. Her short film ‘In Vitro’ (2019) is about Palestine after an environmental crisis, and how the country might be restored using heirloom seeds.

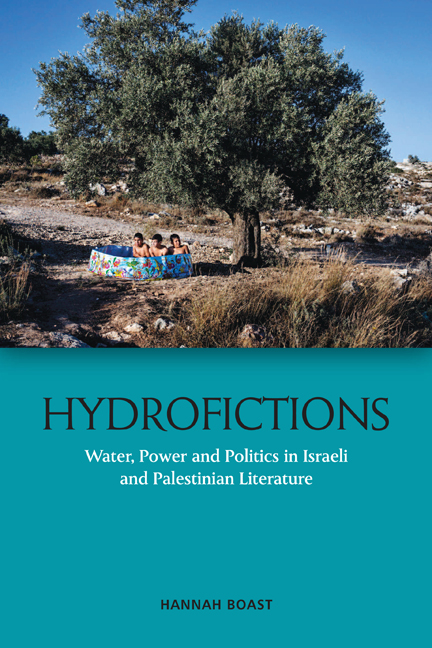

I’m also interested in how visual culture can challenge preconceptions of Palestinians and Palestinian environments. For instance, the cover of my book is a photo from Jordanian photographer Tanya Habjouqa’s series Occupied Pleasures, which she very kindly let me use. It features three Palestinian children in a mass produced childrens’ paddling pool, under an olive tree. Images of water in Palestine could easily be stereotypical: children filling up plastic water bottles from an NGO tanker, deserts, or failing sewage systems. Habjouqa’s playful image of kids in a paddling pool gives us an alternative vision of Palestinian life.

“It’s really exciting when I see my interest in Geography reciprocated by Geographers interested in literature. At the same time, I read that work and find myself wanting more, in terms of a deeper analysis of features like imagery and genre. That’s why I like to have these conversations together.”

Q. How does what you do connect to other disciplines. I know you’re interested in Geography for example and have drawn on the work of Erik Swyngedouw at the University of Manchester.

A. Yes. As I said I did my PhD co-supervised in Geography. Geography scholarship has been very important for my work, so people like Erik Swyngedouw, Matthew Gandy, Alex Loftus, Jamie Linton, as well as work in Anthropology by Nikhil Anand. Gandy and Anand write about water, citizenship and the city, and I’ve drawn on that a lot when thinking about Israel’s destruction of Palestinian water infrastructure and how people experience that in their day to day lives. I’ve also drawn on scholarship in Politics and International Relations. People like Jan Selby whose book Water, Power and Politics in the Middle East: The Other Israeli-Palestinian Conflict I reference in my book title. Also environmental History, people like Donald Worster. His work Rivers of Empire, on water and power in the American West, is a classic for anyone thinking about these issues. I also use lots of work from NGOs, including B’tselem, which is an Israeli human rights NGO, and Palestinian groups Al Haq and Al Shabaka, who have produced invaluable reports about climate change and Israeli occupation.

One thing I might say is that people like Swyngedouw and Gandy often quote from literature, and there’s an increasing interest in literature in Geography. It’s really exciting when I see my interest in Geography reciprocated by Geographers interested in literature. At the same time, I read that work and find myself wanting more, in terms of a deeper analysis of features like imagery and genre. That’s why I like to have these conversations together.

“Rob Nixon calls dams in postcolonial states a kind of ‘national performance art’. They become this way of arriving on the world stage and showing how a postcolonial state is as powerful as its former colonisers”

Q. In terms of big infrastructural water projects, do you see a trajectory from colonial ways of treating nature to what happens during post-independence state building?

I think these colonial projects and the postcolonial nation state building projects are often motivated by common ideas. In both cases, constructing water infrastructure shows a coloniser’s, or a state’s, ability to conquer nature, and to develop and use advanced technologies. Colonial projects like Britain’s water projects in India, for instance, were often paternalistic projects showing the benevolence of the coloniser and their ability to provide for the people. This is something that post independence states also wanted to show, through projects like the Aswan High Dam in Egypt, or India’s Narmada Dam. They become part of a narrative of modernisation.

Rob Nixon calls dams in postcolonial states a kind of ‘national performance art’. They become this way of arriving on the world stage and showing how a postcolonial state is as powerful as its former colonisers. Both stages are part of what Swyngedouw calls ‘hydro-modernism’. In some way these are projects about human emancipation, democratisation, creating social progress through conquering water and nature. But often they have significant consequences for marginalised communities, who are often displaced in these projects of national modernisation, as in the case of the Nubian people after the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

“Literature tells us what water means to people and how it’s intertwined in people’s lives through cultural practices, religious practices, and it literally reproduces our bodies. It can show us our relationship with the environment and resources on a micro scale.”

Q. What about looking to the future, especially in terms of imaginaries. Are there some hopeful or positive reflections?

A. One thing that literature is really good at is showing people’s everyday relationships with nature. Rather than thinking on the grand scale of the nation and the dam, literature tells us what water means to people and how it’s intertwined in people’s lives through cultural practices, religious practices, and it literally reproduces our bodies. It can show us our relationship with the environment and resources on a micro scale. Finding some positive or hopeful stories is part of my Water Crisis in World Literature project. One author I think does really interesting things with water is the poet Rita Wong, who I wrote an article about last year. She thinks about water as something that connects us to other people. She shows how it’s all around us even if the urban environment does its best to hide it. It’s something that our life is completely premised on and she tries to bring these connections to light in terms of thinking how we might value water differently. She also draws attention to the non-human life that is dependent on water, that often gets left out in conversations around sustainable development and the right to water. We don’t tend to think very much about animals and their life in water or reliance on water, but perhaps they also need to be part of conversations about water justice. Wong uses water to think about the collective and our dependence on each other and on the environment, that goes against the individualistic ideas about human nature found in narratives of water wars.

Excerpt from Wong’s poem ‘Flush’, undercurrent, 2016

‘awaken to the gently unstoppable rush of rain landing on roofs,

pavement, trees, porches, cars, balconies, yards, windows, doors,

pedestrians, bridges, beaches, mountains, the patter of millions

of small drops making contact everywhere, enveloping the city

in a sheen of wet life, multiple gifts from the clouds’

Q. Tell us about your next project on hydrosocial futures

A. I’m interested in hydrosocial futures as part of my current book project, Water Crisis and World Literature. Hydrosocial futures refers to the notions of the hydrosocial cycle and hydrosocial relations used by Geographers and political ecologists. Jamie Linton and Jessica Budds unpack these ideas in a way that I find really helpful. Hydrosocial relations is a way of thinking about how water makes the kind of society that we live in, but social relations also shape the way we think about water itself. How we understand water is shaped by our knowledge systems and by economics and politics, and the infrastructure that we use. It’s about thinking about all of those things together rather than water as just H20, existing independently of us in the world.

“The notion of ‘water crisis’ makes us panic that water is going to run out immediately. It implies that we should do whatever is necessary to preserve our water supply, which helps to justify projects like privatisation and securitisation.”

Q. How does culture fit it to this dynamic?

A. Our narratives about water are also part of hydrosocial relations. In my current project, I think about what kinds of narratives about water we want to promote. Water crisis is the narrative that I’m trying to question in the project, that it’s not necessarily that helpful in terms of thinking about how to live with water in a just and sustainable way. The notion of ‘water crisis’ makes us panic that water is going to run out immediately. It implies that we should do whatever is necessary to preserve our water supply, which helps to justify projects like privatisation and securitisation. I look to literature and culture to find different narratives about water.

Q. Your work fits within the general area of environmental humanities. How do you feel that this scholarship can play a role in helping to achieve more just futures?

A. I don’t want to overstate the case for the environmental humanities by saying that reading a novel is going to immediately change the world. But I think the environmental humanities is a good development and a really useful way to draw attention to culture in shaping how we think about nature and for me, water. I think there’s a lot of possibilities, even if I’m not sure what all of them are yet! I’m interested in the environmental humanities as a platform through which I can have conversations with scientists and geographers, and people from all kinds of disciplines, about how we can work together in thinking differently about the environment and the environmental crisis.

I’m also a little bit resistant to thinking about the environmental humanities in such a functional way. One of the frustrating things about literature and one of the good things is that it has unintended effects and you can’t always say that it does specific things. It’s resistant to that logic and those demands. It causes us to think in a different way about environmental change and our goals and our approaches, which can sometimes make it hard to articulate what its value might be when you’re standing next to people who work on politics or in NGOs at a conference. But there’s value in that too, in the refusal of literature to fit a simple model of cause and effect.

Image: Ardnacrusha Dam, Ireland

Q. Finally, have you looked at hydrofiction in Ireland and the written and visual modernisations around something like the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric scheme? People probably ask you about this a lot!

A. I’ve not looked at it so far, but people have been talking to me about it a lot, as you say! I have a growing reading list. There seems to be lots of parallels between Ireland’s water infrastructure projects and those of other postcolonial states in the twentieth century And water has been the focus of controversies and fears more recently, in protests over privatisation and predictions about Dublin being underwater by 2050. I think it’s inevitable that water in Ireland will make its way into my work.