Urban governance, green infrastructure and why Ireland is afraid of the city with Dr Niamh Moore-Moore Cherry, School of Geography.

Q: What draws you to cities as objects of study?

A: I’m interested in cities because they are so diverse and because they are such an important part of the whole ecosystem of the planet. By 2050, nearly three-quarters of the world’s population will live in cities. I’m interested in the dynamism, constant changes and transformations that exist in cities. You can examine so many different aspects of the world; economic, social, cultural, political, identity issues – every important societal challenge- including increasingly environmental issues. Cities are like Living Labs to examine these challenges.

Q: You write about the governance of cities. Tell us a bit about your work on metropolitan governance, and Dublin in particular.

A: My background is in geography and politics. Since my PhD, understanding urban policy development, implementation and outcomes has been core to everything that I’ve done. It’s increasingly apparent that over the last five to ten years, the scale of cities is changing rapidly. Activity is now more concentrated into very large metropolitan areas. Metropolitan governance, political structures and institutions, haven’t kept up with how cities have changed. You have these very large-scale cities and their whole governance is totally fragmented, because it’s based on the size they used to be before.

That generates all kinds of problems for quality of life in terms of planning appropriate transport infrastructure, all sorts of other infrastructures and making coordinated and good decisions. I started thinking about this in the context of Dublin, about poor governance structures and how that played out during the financial crisis; ghost estates, housing in the wrong place, housing unaffordability in some places, empty houses in others. Governance failed to address those issues because it was fragmented. There was no coordination across local authorities in these larger urban settings.

Q: Where does this concept of metrophobia come in?

A: The idea of metrophobia is that, in Ireland in particular, there’s been this reluctance or fear within political structures, institutions and the political class to deal with the reality of an urban future. In order to make that a good quality urban future we need to be planning now, and planning at a metropolitan scale. There are a variety of reasons for that reluctance. It’s related to traditional ideas of rural Irish identity and political culture. Even though rural TDs may say the opposite, there’s been very little focus on Dublin as an entity. We’ve never had for instance, a Minister for Dublin or for Urban Affairs, even though we have had a Minister for Rural Affairs for decades.

It’s also sad that we have this rural-urban binary, this sense that the winner takes all. I would argue if we really focussed on properly managing Dublin, it would have huge benefits for the areas outside of Dublin and for rural areas. Investment would be redirected because we’d know what was sustainable in the context of Dublin. You wouldn’t have the sprawl and the emergence of dormitory commuter towns, that are destroying the landscape in the greater Leinster area. If we could move the discourse to a win-win rather than a rural vs urban that would be a really valuable thing.

“The idea of metrophobia is that, in Ireland in particular, there’s been this reluctance or fear within political structures, institutions and the political class to deal with the reality of an urban future”

– Dr Niamh Moore-Cherry

Q: When you’re looking at urban design and planning is there sometimes a tension between technical and infrastructural issues on one side and engaging people in decision making on the other?

A: I think there probably is a tension in some ways but there are also very strong attempts to bridge that. If you take the whole smart city idea, it tends to be or at least began around sensors, technology, the physical hard infrastructure, without thinking about smartness and why it was there. Francesco Pilla is a really good example of somebody who’s trying to bridge those two things.

Perhaps in terms of decision makers, funding, policy makers, it’s hard infrastructure on the one side versus the soft infrastructure, inclusion, culture on the other. It’s very easy to go down the hard infrastructure side, it’s measurable. Whereas inclusion and participation can be seen as inefficient, it takes time to engage people. I think there is a general shift towards trying to bring the two aspects together. Because at the end of the day the big question is, who are cities for? Why are we building them, and why are we building them in particular ways?

The COVID 19 situation is interesting because it’s really thrown a light on all of that. When you look at the 2km radius, what people have within that, what do they have access to, brings up questions about what kinds of cities we are designing and for whom? A lot of the urban design, early urban design that came out of the United States in the 1920s and 30s, was all about the neighbourhood unit. They used a primary school as a kind of hinterland. What kind of population would sustain a primary school, and you should have all your service within that area. It speaks to sustainability issues, walkable cities, building neighbourhoods, community, all of those kinds of things.

Q: What else can Geography tell us about COVID-19 and its impact?

A: There’s a strong urban focus to COVID. It has massive implications about how we develop cities into the future. High density cities create ideal conditions for the virus to spread. We have to think about the health implications of the kinds of cities we are trying to design. Another thing, to go back to the previous question, is that what is containing the virus is people feeling they can make a difference. Look at how we are actually flattening the curve now, it’s participation, it is a sense of citizenship, that’s flattening the curve. It’s not infrastructure – it’s people.

“When people think about the city and who shapes it, and they are giving out about everything that’s wrong with the city, very rarely do they think that they have the capacity to make change. As urban residents we also have agency as urban citizens. We have the capacity to change the city and to call for the city that we want”

– Dr Niamh Moore-Cherry

Q: You’ve worked with artistic, cultural and community groups in Dublin, projects like Granby Park and A Playful City who address the question of who the city is for. What draws you to those kind of engagements with the city?

A: When people think about the city and who shapes it, and they are giving out about everything that’s wrong with the city, very rarely do they think that they have the capacity to make change. As urban residents we also have agency as urban citizens. We have the capacity to change the city and to call for the city that we want. Cities are that kind of diverse entity that I talked about at the start, they are diverse, they are meant to be colourful, they are meant to speak to all the senses. Artistic and cultural interventions can help that to happen.

It also relates to my governance interests. I’m really interested in this idea of where the formal governance structures of planning and finance meet the informal ones. People are constantly trying to shape or influence their own environment, physically, through artistic interventions, social media campaigns. That space where these two things come together is really nicely understood through things like A Playful City and Granby Park, because to make those interventions in the city you have to engage with the formal processes and regulations and so on. They are interesting stories about how ordinary people and groups can come together and work with formal processes to create something new and different.

It throws up a lot in terms of what doesn’t work in governance structures. One of the things that came out of Granby Park was a realisation that people are interested in making change happen but the City Council is seen as being this impenetrable bureaucracy. People can’t find a way in. Individual people are very well intentioned but it’s the bigger machine that’s the block. As an academic it’s interesting to find out how can you bridge those two things, how can you act as a conduit between policy on the one hand and artistic groups on the other?

For example, I hosted a workshop about 5 years ago on the Temporary City where we got artists and cultural people and policy makers in the same room. What became clear is that the policymakers were trying to help the artists navigate the institutional structures and navigate the regulations. This made me think that at this point the regulations needs to be changed. Everybody is on the same page, the regulation is the barrier. That’s the value of academics working in this space, sometimes we can create those spaces for conversations where people throw off the baggage and see what common ground there is.

“The COVID 19 situation is interesting because it’s really thrown a light on cities. When you look at the 2km radius, what people have within that, what do they have access to, brings up questions about what kinds of cities we are designing and for whom?”

– Dr Niamh Moore-Cherry

Q: Tell us about Mapping Green Dublin?

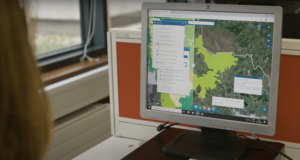

A: Mapping Green Dublin is an Environmental Protection Agency funded project, led by my Geography colleague Gerald Mills and I am co-investigator. We have a great team of partners involved. It comes out of the urban environment work we are doing in the School. The unique thing about geographers is that we can have very different backgrounds. Gerald is a physical geographer and I’m a human geographer so we bridge the natural and social sciences.

The purpose of Mapping Green Dublin is mapping what green infrastructure looks like in Dublin, and to see where there are deficits in the inner city and what can be done to create a plan for those areas. Our project works with community based mapping and supporting the community through workshops and focus groups.

Our goal as part of that is working, we’ve mapped out the entire green infrastructure across the city, we’ve picked a particular area of Dublin around Dublin 8 around Inchicore, Kilmainham, Rialto, we’re particularly interested in. We’re working with community development organisation there, a range of organisations within communities that traditionally would have seen themselves as marginalised and have been marginalised. We will develop or identify the strengths in terms of green infrastructure but also the deficits, how they might be addressed. The project will create a neighbourhood greening forum and a community greening plan that we can then bring to policy makers, in the hope of getting a project in action.