Farming and daily life in prehistory, organic geochemistry, and ecological thinking in Archaeology with Dr. Jessica Smyth, School of Archaeology.

Dr Jessica Smyth

Assistant Professor

UCD School of Archaeology

UCD Profile

Q: You use molecular analysis of archaeological remnants in your work which comes from Chemistry. What led you to that and are these methods quite new to archaeology?

My first foray into the hard sciences was in 2011 with a Marie Curie Intra-European Fellowship at the University of Bristol. I was based at the Organic Geochemistry Unit, in the School of Chemistry for two years, 2011-2013, where I was very much immersed in chemistry and laboratory work and got my first real experience of being part of a research group. Humanities and Social Sciences research can be very lone scholar research, so this was a real eye-opener and a very steep learning curve.

My reasons for wanting to go there were that I’d done my PhD on Neolithic settlement and domestic architecture in Ireland, and I was keen to look for more ways of mining information about daily life in prehistory. Pottery first appears in Ireland in the Neolithic, as it does in many places around the world. There is a very interesting mix of the social, cultural and technological in pottery and people hadn’t really done much with the Irish material beyond work out typologies and chronological sequences. The Bristol group had done a lot of work on British prehistoric pottery, analysing the organic residues absorbed into the vessel walls of the pot, and I thought why don’t we do this with Irish pottery.

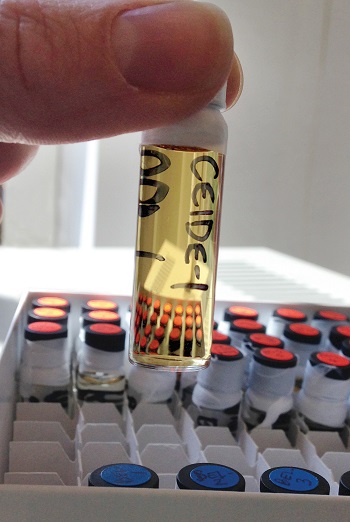

“What I was investigating were the ancient lipids or fats absorbed into the vessel walls of the pots through processing – heating, cooking, storage and so on. Through gas chromatography and mass spectrometry you can compare trace amounts of these archaeological lipid mixtures with modern reference lipids from a range of plants and animals. If archaeological animal fats are present, measuring the stable carbon isotope values of the main fatty acids surviving – palmitic and stearic acids – can tell you the origin of that animal fat, so ruminant or non-ruminant, and milk fat or carcass fat”

– Dr Jessica Smyth

Q: So the Bristol Group had laid the groundwork of doing these lab-based techniques in the UK but they hadn’t really been used here?

Exactly, almost nothing like that had been done before in Ireland, and certainly nothing on a large scale. Archaeological science is very strong in the UK, with some amazing techniques and analysis developing over the past twenty, thirty years. In some ways, Irish archaeology has been quite slow to capitalise on the potential there, of our nearest neighbour, but that is changing rapidly. A mobility scheme like the Marie Curie IEFs (now Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowships) was so important for encouraging that sort of knowledge transfer and created a whole new generation of archaeologists working between the humanities/social sciences and science. At Bristol I could completely immerse myself in chemistry and science, and the archaeological material I had chosen to study generated some fantastic data. I think that was a bit of a lightbulb moment, because the evidence I found for ruminant dairy fats in pottery, you can’t normally access via animal bones because archaeological bone doesn’t survive very well in Irish soils. So this was a kind of oh my gosh moment – there’s a whole suite of molecular-level information that you can tap into.

Q: How old are the pots you were working on?

Five to six thousand years. What I was investigating were the ancient lipids or fats absorbed into the vessel walls of the pots through processing – heating, cooking, storage and so on. Through gas chromatography and mass spectrometry you can compare trace amounts of these archaeological lipid mixtures with modern reference lipids from a range of plants and animals. If archaeological animal fats are present, measuring the stable carbon isotope values of the main fatty acids surviving – palmitic and stearic acids – can tell you the origin of that animal fat, so ruminant or non-ruminant, and milk fat or carcass fat. It’s amazing. It was so exciting to identify that for the first time in these very old pots.

Through my PhD work and later research I had looked a lot at settlement archaeology and the Neolithic settlement remains uncovered during infrastructural projects – motorways, pipelines and the like – and was very familiar with the type of material that would come from these sites like scrappy bits of bone, crumbly pieces of pots -stuff that was not particularly well-preserved. Compared to similar material from other parts of Europe, I think there was an attitude that this sort of stuff wasn’t very informative and you couldn’t do much with it. At Bristol, I began to appreciate the amount of biomolecular information that was still there and that the temperate, wetter climate in Ireland had preserved some of these biomolecules really well, particularly the lipids. I realised this was brilliant. It levelled the playing field, and you could start to look at these questions of diet, subsistence and economy on much more challenging material

“If you genuinely are serious about being interdisciplinary and not just bolting on a fashionable topic or field of enquiry, you need to approach things with humility and an expectation of feeling out of your depth, as well a desire to do that translation work that enables different disciplines to meet in the middle. A humanities critical self-reflective approach with a science hypothesis-based approach is a really powerful combination, but it takes effort.”

– Dr Jessica Smyth

Q: Did you do science in school? What was it like working in this very interdisciplinary way?

I did chemistry for the Leaving Cert, but yes chemistry in Bristol was quite a different subject. I think even the periodic table had been reshuffled in the meantime. It was a huge learning curve and really challenging at times, but I’m glad I attempted it myself and didn’t ‘black box’ things, which is easy to do these days in research collaborations. It fundamentally altered my way of approaching problems and gave me a huge respect for proper interdisciplinarity – where all partners acknowledge their limits as experts and respect the knowledge of other experts. There is so much sub-discipline specialisation today, you can’t be an expert in everything, that would be ludicrous. You have to work more smartly.

If you genuinely are serious about being interdisciplinary and not just bolting on a fashionable topic or field of enquiry, you need to approach things with humility and an expectation of feeling out of your depth, as well a desire to do that translation work that enables different disciplines to meet in the middle. A humanities critical self-reflective approach with a science hypothesis-based approach is a really powerful combination, but it takes effort.

Q: Did these new techniques bring new insights?

They did and they didn’t. Obviously, Ireland today is a huge farming economy, and dairy economy, so I think people already assumed these modern practices had their root in some ancient way of life. In that sense it wasn’t a surprise, more a confirmation. However, there has been a fair amount of debate among archaeologists about when exactly that happened. Some people would pin dairying as part of a secondary products revolution that only developed in the Bronze Age, i.e. when animals were first domesticated in the Neolithic they were used for their meat only, but as farmers got to know their animals better they realised you could systematically exploit cows, and sheep and goats, for their milk. I was never quite convinced by that theory – it’s quite patronising to early farmers!

My research provided the first direct evidence for dairying in Ireland, and it was happening as soon as farming appeared on the island, so no warm-up period. The people who brought these new animals to the island in boats already knew how to milk them. The pots tell us that, even if the traces of those first dairy herds are long gone. It sounds odd now, but back beyond our extensive early medieval sources – which are full of references to milk and dairy products – there was just no way of telling how far back in time dairying went. And compared with other regions of Europe in the Neolithic, Ireland is super milky. Ruminant dairy fats are by far the dominant fat type in these pots, and suggest milk was important in these people’s lives, or ‘foodways’ as archaeologists like to call it – a term that recognises both the cultural and nutritional aspects of food.

Q: You won an Irish Research Council Laureate award for your project, Passage Tomb People. Tell us a bit about that. Does it fit in what your earlier interests in settlements and daily life?

I suppose it is an extension of what I’d been working on before. I’m still really interested in daily life in prehistory. Traditionally passage tombs, and megalithic monuments in general, have been held up as special, different, separate or disconnected from daily life, and they’re still presented that way to the public I think, even if most archaeologists now appreciate the range of functions they served in the past. They weren’t just tombs, boxes to put dead people in, but places to navigate and make sense of the world – like any architecture, really. The disconnect is in part related to issues of heritage management, but also due to archaeologists failing to de-mystify this period of our past, and I wanted to explore more systematically and more explicitly how these monuments linked in with everyday life.

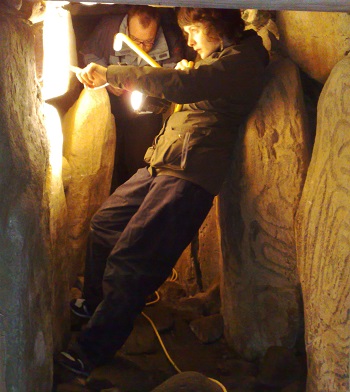

Calling it Passage Tomb People was very deliberate, I wanted to foreground the people, using this molecular level archaeology to target already excavated remains. That’s another deliberate rationale or approach – there’s already quite a lot of stuff out of the ground, that’s been dug up and is now in the archives of museums and other institutions that can be tapped in sustainable or semi-sustainable way. Most archaeological science techniques are minimally destructive, with sample sizes getting smaller all the time. While excavated remains are a finite resource, if you sample ethically with clear research questions, you can extract an amazing amount of additional information from already excavated material. I was interested in going back to these excavated sites, some of them iconic sites, like Newgrange, which people would be very familiar with in certain ways, and giving some wider context on how they connected to people, settlements, community, and the environment.

Jessica Smyth at Knowth Passage Tomb

Some recent research has questioned whether farming, when it starts out in the Neolithic period, was very successful. In several regions, Ireland included there’s evidence of dips in activity, represented by a lack of radiocarbon dates, a few centuries after farming appears. Some researchers have suggested that farming didn’t really get going until the Bronze Age. If that were the case, why do you get really big monuments like Newgrange being constructed, right at the point when some people are arguing farming wasn’t really working out. Is there something behind that? Are they throwing these big monuments up because they’re scared? Or is it because they’ve got loads of resources?

On the project we have a full time postdoctoral researcher, an archaeozoologist, overseeing the osteology work packages – sampling, analysis and interpreting patterns across our three study areas – Ireland, north Wales and Orkney. There is also a PhD student in Bristol who is undertaking the organic residue analysis on the pottery as well as radiocarbon dating. We also are lucky to be collaborating with a team of experts across the UK and Europe, specialists in multi-isotope analysis and proteomics, as well as local archaeologists advising on good assemblages and sites to target.

Q: I saw a conference paper you wrote with Meriel McClatchie and Graeme Warren which talks about the transition between Mesolithic and Neolithic being more blurry and complex than is sometimes represented. Why do you think things get simplified in this way?

Detecting change and transition in the past is always difficult. The Mesolithic and Neolithic are modern terms, classifications we have put on past remains to try and describe what we’re encountering in the archaeological record. So, Mesolithic broadly means hunting, fishing and gathering resources, accompanied by different kinds of tool technologies, material culture and social organisation. The Neolithic as I’ve mentioned is strongly associated with a farming way of life, and in Ireland new forms of technological and cultural expression such as pottery, timber houses, megalithic monuments, as well as new plants and animals.

For a long time, these changes were viewed as a pretty tight ‘package’ of innovation that arrived in Ireland around 4000 BC, but increased resolution in radiocarbon dating, along with smarter choices about what we choose to date in the first place, have made this sharp line much more blurry. It’s common to a lot of observed data I suppose – the more you zoom in on something, the more complicated and intricate it becomes. I think now, a lot of debate is on properly balancing this narrative of change and transition. So, on one hand, there appears to be some quite rapid processes – for example, the appearance of timber plank-built houses around 3750 BC – or seemingly quite clear delineations – hunter-gatherer and Anatolian/farmer-type genetic signatures – but this is set alongside more gradual processes and elements of continuity. We have cattle bone (a non-native species) from Ferriter’s Cove in Co. Kerry several centuries before any other indications of farming activity. What was it doing there? People had to have been making international sea crossings in the Mesolithic and were likely in pretty regular contact with one another before farming was ever adopted.

In that paper we also suggest that the evidence for animal husbandry and dairying in Ireland may pre-date arable agriculture and the evidence for cereals, a pattern also beginning to emerge in Britain. The tendency for simplification and a ‘grand narrative’ is always there in archaeology, as in other disciplines, but we need to resist this as much as possible, even if it doesn’t always make the snappiest publication titles or press releases!

Q: I was surprised to learn that pretty much all the large mammals we might associate with the Irish countryside are not native

Yes exactly. Our beloved cows are pretty late arrivals! We have quite a reduced range of fauna, smaller than Britain, and smaller again than the European continent, where species didn’t seem to make it across before the land bridges disappeared or were here and died out. What I find fascinating is the potential impact of fairly large mammals, like cattle, on an island environment or just an ecology that hasn’t had that species before. What sort of effect did that have on the Irish landscape? It’s back to that idea of ecological thinking really.

“I think what makes archaeology especially powerful as a discipline is that deep time aspect. It can really remind us that lots of things that we view as unchanging, like rural landscapes or traditions, are actually so recent. The past is really different and really weird.”

– Dr Jessica Smyth

Q: For an archaeologist what does ecological thinking mean?

I think it’s about expanding our thinking beyond the human. Paying more attention to other organisms, particularly animals. It sounds obvious to say it but it’s not a relationship of dominance. There’s a concept that’s growing in popularity among archaeologists, that of ‘entanglement’, tackled recently in a book by Ian Hodder, but chiming with lots of current thought in philosophy and anthropology. It’s basically how things, they could be things we view today as ‘inanimate’, or animate things like animals, kind of force you to act in certain ways, because they have their own qualities and their own agency. It’s a bit naïve to think of just humans imposing their will and their agency on everything from the outset. I suppose lots of our language around farming or perhaps earlier language about farming is about domesticating, seeking control over the land. It doesn’t work that way because if the weather isn’t suitable particular plants won’t grow, or if you can’t gather sufficient fodder for overwintering your animals they’ll die. It’s part of that broader conversation around humans and nature, realising that western, post-Enlightenment nature-culture divide is only one way of viewing the world.

I think what makes archaeology especially powerful as a discipline is that deep time aspect. It can really remind us that lots of things that we view as unchanging, like rural landscapes or traditions, are actually so recent. The past is really different and really weird. As humans, we constantly project our own contemporary views back onto the past, and as societies we forget things – major, life-changing events – scarily quickly. Even if you think about something like the current pandemic, and people are understandably jolted by that. But there was a major pandemic in 1968 as well, that killed millions of people worldwide. That’s a little over fifty years ago, yet that memory has been pretty much erased. I think archaeology is very good at reminding us about diversity in our population today but also throughout time, and not to be complacent, not to assume things were always this way, and things can happen dramatically, very quickly and can be utterly different from what they are now. It’s a bit of a wake-up call, if you like!

Q: From your work on early farming, human animal interactions and daily life, what’s relevant from an archaeological perspective to sustainability and environmental research today?

In archaeology we think a lot about change, but also what made things work in certain times and periods. For me, that early dairying activity is interesting because today we have a multi-billion euro dairy industry that is tied very closely to our national identity. We also have a very high lactase persistence rate in the Irish population, in common with a few other northwest European/Scandinavian countries. If you look at that rate globally, it’s massively variable, some parts of the world are not and our high lactase persistence rate would point to a strong relationship with milk products in our past. Comparing this current day scenario with the pieces of evidence emerging from prehistory I do wonder about that trajectory – if indeed it is a trajectory and the ultimate suitability of Ireland for dairy farming. It’s temperate, good for grass, it doesn’t have the severe winters like the Continent. Is that just an example of something, a way of life, that just really clicked for this part of the world? An example of niche construction?

I think the archaeological evidence also brings an important angle to examining the cultural embeddedness of milk today in Ireland, and the paths to that embeddedness. Obviously, lots of that work has been achieved recently, from the mid-20th century onwards, but you can identify that relationship in the 17th century texts of English commentators and travel writers, and again in the early medieval texts. Milk certainly is a very useful food product, it can be stored, it can be preserved, it’s very versatile and nutritious, you can survive on it and little else if needs be. Lots of our population has done this in the recent past. Extending that back into the Neolithic, nearly 6000 years ago, is of course a huge jump in interpretation and you have to remind yourself that today’s dairy industry and that form of self-sufficient farming are two very different things, both culturally and environmentally. While I’m not sure archaeologists, especially prehistorians, would have the resolution of data to inform arguments about farming sustainability and tipping points, I think we can contribute a lot to the debate around milk consumption, and the ‘naturalness’ or otherwise of that phenomenon. exploring the cultural embeddness of something like milk.

The Irish Dairy Board have mounted big campaigns to promote milk’s ‘naturalness’ in recent years, perhaps appealing to Ireland’s long relationship with dairy

It’s a huge lobby, certainly, with a lot at stake in terms of the Irish economy. We have to be careful about projecting the industry of today back towards some ideal farming past where Irish people are natural milk consumers and producers, like this is our destiny. There is no denying that milk products are very visible in the Irish archaeological and historical record at certain points in time, but our use of that information today depends on how we want to frame our past and our identity. There’s at least 10,000 years of human occupation on this island, likely more, and milk is only around for 6000 years or so. Are Mesolithic communities less ‘Irish’ or less authentic for falling outside of that dairying phenomenon? In terms of resource exploitation globally and through human development as a species, milk is even less part of that picture. So I think it depends on what we as modern societies want to identify with, and why. Archaeology can provide that context to challenge current paradigms.