Writing, nature, sound, language, ecology, climate anxiety, environmental humanities and interdisciplinarity with Dr. Paula McGrath, School of English, Drama and Film

Dr Paula McGrath

UCD School of English Drama and Film

UCD Profile

Q. In your role at UCD you teach creative writing and explore environmental issues, and outside of this you do your own creative writing. Tell us about how you combine the different aspects of what you do.

A. They are very much intertwined. I spent a whole school research talk recently trying to do a Venn diagram on this. It’s quite difficult to know where to jump in. The writing came first. Bull island, in Dublin Bay, is central to a lot of what I do. It’s at the end of my road – I’m very lucky.

The IPCC report in 2019 coincided with a stage of my research where I had become completely disillusioned with narratives where the protagonist finds solace in nature. I was thinking, well actually, this should be the other way around; nature is in trauma and it’s our fault. That kind of flipped everything.

My first response was despair; I found myself asking why am I not a marine biologist, then my second response was then, what can I do? I was at the time an occasional lecturer here and I was really lucky that at the same time John Brannigan and Tasman Crowe were working on their Cultural Value of Coastlines project. Some of their research was based on Bull Island and it aligned with my interests.

I wanted to develop a module for undergraduates and take them out to the island, a practical hands-on course that would include scientists as well as humanities and creative writing, but essentially a creative writing module. John and Tasman were super helpful.

Q. To go back to your own writing, perhaps it is hard to analyse yourself but what kinds of themes have featured in your novels, in your writing? How does the natural world feature, what kind of role does it have?

A. As a writer, one of the problems with the environment and fiction is that if I set out to write a novel that’s about the environment then it’s going to be a dud as a novel, preachy or too ‘on the nose’. It fails on every count, then, because who wants to read a bad novel? A novel, in my experience, has to start somewhere else – a character, a place, a line of dialogue – with themes emerging through the writing process.

Q. When something is too didactic?

A. Yes, that’s what I’m always scared about. That’s what has been a problem. I never set out to write a novel like that. My fiction would generally be character led. I might have an image of a person, so the most recent thing I’m working on had an image of a person sitting in a deck chair in a back garden. A woman of a particular age, I was able to figure her out quite quickly. The rest all followed from there.

It has an environmental theme, I would say, but it didn’t start with one. It emerges, then you enhance it, and try to balance it with the story, and with what the characters want to do, themselves. It’s about whether I can get that right or not. I don’t know if you’ve come across Amitav Ghosh’s Great Derangement, he talks about the problems of writing fiction during the climate crisis. It’s a challenge for fiction. I think it’s easier for poetry. Also in young adult writing, or children’s literature, didactic is fine. In those forms, it’s the way to go.

Q. What are you drawn to when you write about the environment, is it sensory, or more about mood?

A. All of those things. Sometimes setting is just a place to put my characters. A coffee shop or a street. Trying to capture places is another challenge. I spend all this time on Bull Island and I think about it all the time but when I sit down to write about it, it’s a question of what’s too much, what’s too little, how do I do it?

It’s like when you’re at a party and you realise you’ve just bored someone stupid because you’ve been going on and on. Environmental concerns can’t be a separate thing, a chunk sitting in the book, it has to be woven in with everything else. That’s the balance, that’s the editing process, and what I like doing I suppose.

Q. Do you do lots of drafting and redrafting?

A. Yes. A lot. Then because you’re constantly deleting and rewriting as you work on a document nowadays, there’s probably hundreds more drafts than you actually give names to. It’s constant.

Q. In your UCD biography page you talk about facilitating creative writing rather than teaching it, have you done other kinds of teaching as well? Is creative writing different?

A. I think facilitating is the best word for it. The way I approach it anyway, it’s a holistic thing. I need the physical space to be conducive if at possible, which is not always the case depending on what room you’ve been given or whether you can move chairs around, for everybody to feel that they can participate equally, for everyone to feel comfortable.

When you’re writing creatively, even if you’re making a story up, if it’s fiction, it’s still a part of the author in a way that’s not necessarily the case if you’re let’s say writing about Joyce or another writer. It feels like you’re entering into a different kind of relationship with the students. At least I feel that anyway.

Trust has to be built up, before they are willing to share work, to share feedback that’s in any way useful or honest. I mean, they can very easily say to each other, oh I love everything you do, but while some validation is nice, as feedback, that’s useless. It’s about setting up and figuring out whether small group work is useful, or pair work, or presentations. It’s a lot of active learning.

I would say other subjects now use methods that we would have been using in creative writing all along, sharing work and sharing opinions, much less of the person standing at the podium, talking at the students. There’s very little of that.

The only other subject I taught was yoga, and with yoga actually, there are some similarities. It is actually a very creative thing to do, to teach yoga, you’re looking at every individual, you’re trying to make sure bodies are placed correctly, safely, you might be making physical adjustments, less so now but that was very much the norm. It was really hands on, but it was very individual because everyone has a different body, with a different history.

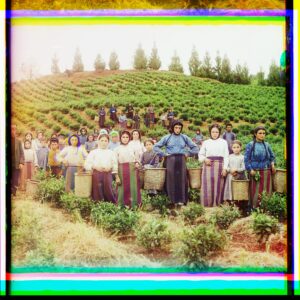

Students on a rainy salt marsh walk on Bull Island (credit: Paula McGrath)

Q. Your ‘Writing the Environment’ module that you already mentioned, on Bull Island. What’s involved in the module? How can writing, sound, language connect us to the environment?

A. Well I started with the island and the idea that connecting with this particular place meant connecting with the planet. The students contextualise what they are doing with nature writing in the past and the present, and they do their own writing. There are critical and creative aspects in the classroom, and then the workshops. Around Week Five, we do something called ‘deep mapping’, where the students draw maps of the island and they start to add in everything they have experienced in relation to the island to the map but also hopefully drawing on stuff that they have covered in talks and lectures prior to that.

They’re adding to this map for the whole semester and then they use ideas and whatever they’ve put on there. It looks like a map, it’s a sketch that they can colour in, make three-dimensional, they can add whatever they like, they could add a little poem, they could write an idea, a line that they overheard when they were on the island.

They will already have done one field trip by the time they draw their maps, so they are drawing the island from memory. That’s always hilarious, because when you’re walking a place, you tend to have a distorted perspective. During their field trip, they meet the island manager, who gives them a lot of information on the island’s history, flora and fauna, managing a nature reserve – a broad overview. They can add some of this information to their map. Another week, they do a soundwalk, so they might be working on sound-based poem or something like that, and they can again add to their map.

Q. What is the soundwalk? A kind of listening exercise?

A. Yes, a traditional soundwalk is a listening exercise, literally just giving up your time and listening as you walk. You listen for a variety of sounds, and you get some prompts – what is the loudest sound you can hear, the furthest away, what sounds can’t you hear and why can’t you heard them, things like that. Just to think about the different senses, how we experience place through all of the senses.

Then they have their ecology walk, and we talk about futures. That’s a bit grim because they realise what’s coming. I set them an exercise which asks them to think about Bull Island, which may have disappeared in seventy years’ time. They always start with, well Paula won’t be there but…

The field trips bring a real kind of hands-on aspect, something really enhanced by being there and not on campus. They go there three or four times, and because it’s a very particular place and it’s very vulnerable to rising sea levels and so on, it is a very vivid way of presenting and understanding, naming and communicating climate change.

Q. Are there many creative writing modules in the School of English, Drama and Film?

A. We have a full undergraduate programme in English with Creative Writing, so it’s about one fifth or sixth of the overall degree. Then there’s an MA and an MFA, and we also offer PhD supervision.

Q. Are most of your students already on that track, or would they all have an interest in Creative Writing?

A. Mostly, but not all, and that’s interesting. Because the ones who haven’t done creative writing, in some ways they’re more open because they haven’t had that process of editing and so on, so they are quite uninhibited. Then in other ways it’s quite daunting for them to sit down with a more experienced group. I find that in groups where creative writing students are mixed with other students, they actually teach each other, they learn and teach from each other.

Q. Is Bull Island in some ways man-made?

A. Sort of. It’s 200 years old. It was formed by natural processes following the construction of the Bull Wall. The Bull and South Walls were built to prevent silting in Dublin Bay, and they caused the tides to moving in a different way. There was already an existing sand bank and it just started to accumulate. It’s still growing, there’s also erosion but it’s growing more than eroding.

There’s also an island that the students are always really interested in, called Clontarf Island, that disappeared in a storm one night. There was just one little dwelling on it, it had been used for all sorts of funny things like quarantine purposes, for instance, but then a storm finished off what was there. It triggers their thinking – this was there and now it’s not, Bull Island wasn’t there and now it is, so what’s the future?

Kite surfing on Dollymount (credit: Paula McGrath)

Q. Your PhD touched on the topic of trauma. Do you find that that framework is supportive to teaching and research on climate and environmental topics?

A. My PhD was on representations of trauma in fiction, so I was looking at how we write trauma, how we put it on the page. I was looking for new methods to do it. Because there’s a tendency to fall back on modernist techniques, you know, fragmented texts, gaps and elisions in the text, flashbacks, to try to mimic the traumatic event.

I thought, well grand, but I’m no longer shocked when I read that, I’m no longer in it, I feel like it’s worn out. I was looking for other ways. I wasn’t particularly successful, but it was interesting. I was looking at the trauma narrative and the healing of the protagonist in nature. I think everyone knows The Secret Garden, the children’s book where they end up going into the garden where they heal and grow and everything blossoms.

It’s lovely except that it doesn’t really work for me as a fiction narrative anymore because of the climate crisis. How dare we go off and feel better in nature while we toss our rubbish into the ocean? So that was perplexing me by the end of the PhD.

Q. Do you feel that creative writing can help with climate anxiety?

A. I’m very wary of saying ‘creative writing is great, it’s therapeutic’. In psychiatry and psychology there are some approaches that include going into nature. But there’s a difference between fictional narrative and actual clinical practice.

Obviously, many if not most of us feel better when we go into nature. But one of the points that several of these studies make is that we need to acknowledge the emotional disturbance, that this anxiety needs to be acknowledged and recognised, and that one of the treatments that they feel helpful for allowing patients to do this is what they call a kind of creative writing, emotional writing. They’re doing studies on this.

One of the other suggestions is that people get involved in community action, actually doing something, for climate anxiety alleviation. That helps, writing helps. I’ve experienced this personally but I wouldn’t make any claims, I wouldn’t suggest it to a student and say, this will make you feel better. But there are resources we can point students towards.

Q. Do you find it helpful to think of your writing within the bracket of environmental humanities? Or to connect to other disciplines?

A. Yes. I had my module and it wasn’t approved, then I found the environmental humanities research group at UCD. And it was kind of scary, because when you’re writing novels and doing place-based research you are not sure where you belong there. I went along to a symposium and found it to be the most open and welcoming community.

As I said earlier, I despaired that I wasn’t a marine biologist or something useful, but I have come to realise how the humanities have a part to play. I had my own angle, I can write books, but how many people read literary fiction? Not that many. What else is there? So then to find people in humanities and social sciences as well, Classics, everything, and get to meet them. That led into other things, I applied to British Academy seed funding to do a project, Environmental Inscriptions, which is about walkshops and again connecting with place, and through place to planet.

Q. Do you enjoy connecting to STEM disciplines in your work?

A. Yes I do it all the time. I benefit hugely from going to the Earth Institute coffee mornings. I go whenever I can, when they grab me, and just about everything does. One slightly perplexing situation is that I’m enthusiastic, I’m there and I want to engage, and I get that back as well from scientists, people are interested. But it’s more like I’m reaching out asking people to teach on my module rather than the other way around. There is a group working on that to try and exchange pedagogies.

Then the other area is funding. If someone is doing a science funding application, they don’t usually ask for involvement from the humanities. It can be a bit a bit unequal, perhaps lip service being paid to the humanities rather than involvement at a bigger or political level. It doesn’t always filter down.

Q. It feels like those deeper collaborations takes a lot of time and effort?

A. Yes, it’s the qualitative approach and it doesn’t add up so neatly on the kinds of hard data that you’d like to put into a report at the end. I can see the problem, and I can see where it come from. It’s hard to match up the two, even with the best of intentions, but it’s doable and we just have to keep doing more of it.

Paula McGrath has written two novels: Generation (2015) and A History of Running Away (2017). You can find out more about her writing on her website.