Sustainability, agriculture and food production, waste management, circular economy, culture, heritage, research communication and public engagement with Associate Professor Tom Curran, UCD School of Biosystems and Food Engineering.

Associate Prof Tom Curran

UCD School of Biosystems and Food Engineering

UCD Profile

Q. What was your route in terms of your studies and research in Biosystems and Food Engineering?

A. Originally I studied engineering in UCD. I specialised in Agricultural and Food Engineering, which tied in with my background having grown up on a farm. I could see at that time there was going to be a bigger demand for food with a growing population, and there was a need to incorporate sustainability into that. This was back when sustainability wasn’t a big word.

In my third year, that summer I went on work experience to Austria. It totally changed my perception and had a big impact on me as an undergraduate. It was through an organisation, originally through FÁS, called the International Association for Exchange of Students for Technical Experience. If you had three years study done in a technical subject you could apply. It was basically an internship.

I got a placement in a laboratory doing very boring work in a very nice part of Austria near Lake Constance, where Austria meets Germany, Switzerland and Liechenstein. That had a big impact on me, not just the natural environment and the beauty of the area but how so far ahead of us they were in terms of environment. They were already way up on recycling and composting and things like that.

When I graduated, I worked in the meat byproducts industry, basically dealing with the leftovers from the meat industry, making meat and bone meal and tallow from it. I was exposed to a lot of environmental issues through the job as it was a small company. I was really in at the deep end, dealing with architects and county councils and I could see major issues from an environmental point of view. That grew my interest in the environment, further to my experience in Austria.

After that I did a master’s in environmental engineering at UCD, that built on my practical knowledge I had learned on the job. After the master’s I worked at another company in the meat industry, a bigger company, which gave me more exposure to environmental issues. By that stage the EPA was established and I became more familiar with the legislation at a national level.

I worked in that company for three years, then an opportunity came up for a temporary appointment in UCD. My mentor at the time was the late Professor Vincent Dodd, who was the Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture. He inspired a lot of people as well as myself to work on environmental issues over the years. My job contract was extended and I was given time to do a PhD on odour nuisance while I was working.

“Agricultural engineering might be typically associated with the farm level, whereas biological systems, biosystems, connects with ecosystem, ecology, forestry”

Q. Was it called the School of Biosystems and Food Engineering at the time? As a title, is this common or unique to UCD, what are the origins of the discipline?

A. At that time, it was the Agricultural and Food Engineering department but it was basically the same discipline. Biosystems and food engineering is quite unique to UCD. The origins of the discipline go back around a hundred years to America. Agricultural Engineering as a discipline was formed from mechanical engineering, applying mechanical engineering to agriculture and food production. You had mechanisation of farms, going back a hundred years or so, where you had tractors and other machinery harvesting crops in the field, then it became more mechanised in the later stages of food processing in factories and so on, with a big demand for consumer products. The origins of agricultural engineering is that whole process of harvesting from the farm to the fork. My area would have been the environmental aspects of that.

Q. Would you say the biosystems aspect is more recent?

A. Yes that has only come in more recently, in the last twenty years or so. It has taken the lead internationally, particularly in American universities, where the term biosystems or biological systems has a wider appeal, rather than the narrower focus of agricultural engineering. Agricultural engineering might be typically associated with the farm level, whereas biological systems, biosystems, connects with ecosystem, ecology, forestry. It’s still called agricultural engineering in some places but biological systems or biosystems is a broader term. You’re going into aspects of biology and human biology in some cases as well.

“The bioeconomy covers the sustainable use of biological resources from farming, food, forestry and the marine. It saves energy, minimises pollution and has benefits for climate action and biodiversity.”

Q. What would be some of the current big challenges being explored in this field?

A. The whole area of sustainability is the big one. It’s a global issue between climate change and biodiversity loss. They are the big issues at the moment, human existence. It’s at a critical level, especially over the last year when you see the trends in climate change, it’s very worrying. We have to look at it from the point of view of a positive message that we have solutions and they can be biologically based solutions which can help mankind. That’s the way we have to look at things. Things can be seen as quite bad from a climate change and biodiversity perspective, but we need to bring people on board and spread a positive message.

Q. You work a lot on the bioeconomy, can you explain to us a little bit about what the bioeconomy is and some of the benefits?

A. The bioeconomy covers the sustainable use of biological resources from farming, food, forestry and the marine. It saves energy, minimises pollution and has benefits for climate action and biodiversity. I am part of the SFI funded research centre BiOrbic, which is Ireland’s national Bioeconomy Research Centre.

“Bioeconomy is a very broad concept, so in BioBeo, we came up with five themes, so 1) the food loop, 2) forestry, 3) life below water which is also a Sustainable Development Goal, and 4) outdoor learning which is a big emphasis because it helps you to go outside and engage with the environment, and finally 5) interconnectedness, how everything connects together and how what we as humans can have a major knock on impact on other things.”

Q. Would you say in general bioeconomy is well understood by people?

A. No, it’s not well understood. Many people have not heard of the bioeconomy. I asked a class in UCD recently if they had heard of the concept and I would estimate that less than 5% of the students in the room had come across it previously. From talking to the students, and to adults as well, we realised very few people have heard of the term bioeconomy. In the Horizon Europe funded project BioBeo, which I lead, we are targeting children, so we’re trying to use the language that they understand and break it down into smaller terms they can relate to.

Bioeconomy is a very broad concept, so in BioBeo, we came up with five themes, so 1) the food loop, 2) forestry, 3) life below water which is also a Sustainable Development Goal, and 4) outdoor learning which is a big emphasis because it helps you to go outside and engage with the environment, and finally 5) interconnectedness, how everything connects together and how what we as humans can have a major knock on impact on other things.

One of the things we need to emphasise in general is sustainable consumption. An example of this for the recent BioBeo festival in Brussels, we were thinking of having our presenters at it wear t-shirts, which is typical for festivals, with the BioBeo logo on it. Then having thought about it a bit more we were looking at alternatives, like a wristband or something that’s more sustainable. We ended up with a sustainable fashion competition where people could wear something that they bought in a charity shop, rather than producing something new. It’s all about sustainable consumption. It’s a big thing we have to change our mindset on.

Q. Tell us about the BioCultúr project you’ve recently started, which brings in social and cultural approaches to changing things?

A. What I’ve seen particularly in the past five years or so as I’ve gotten more into the communication of research results, is that bringing people on board from a wider society perspective is really important. We have great technical solutions but if you don’t bring people on board, it’s very hard.

BioCultúr falls within BiOrbic’s enabling action, under education and public engagement. It is similar to BioBeo but it is more about outreach and community, to connect to people through language, culture and heritage. For the bioeconomy to succeed one of the key people who might benefit from it are people in rural and coastal regions and they are often marginalized people, low population densities, where a lot of people have left for the cities, or the Gaeltacht areas, Irish speaking, and other rural regions would have certain dialects, words for things that are quite unique to those regions. We’re trying to emphasise that.

If you go in and don’t take account of the culture and language of the region, you’re immediately seen as imposing something, even though they might stand to benefit greatly from it. Certain areas of the country would have different cultures in terms of accepting the bioeconomy, particularly forestry. For instance in Leitrim many people are very much against it, whereas in Wicklow there’s more of a culture of people working in forestry.

“‘It’s estimated that maybe two thirds of the population will live in cities by the year 2050, so more and more people are living in cities, cities are getting bigger. The older cities have old sewage systems underground, so that’s going to be more challenging, there’s going to be more maintenance problems”.

Q. You’ve done a lot of work on waste management including FOG – fat oil and grease – management. Do you think this issue is improving in general?

A. Cities are dealing with it better I think than in previous times. It’s still a challenge in the UK because of the wording of the legislation where the requirement for having grease recovery equipment is open to interpretation. That’s why it’s like ground zero in London, where there is a high population density with many restaurants and an ageing sewer network. When you look at the global population, it’s estimated that maybe two thirds of the population will live in cities by the year 2050, so more and more people are living in cities, cities are getting bigger. The older cities have old sewage systems underground, so that’s going to be more challenging, there’s going to be more maintenance problems, like the brickwork in London systems for example. The key thing is going back to waste management at source – if you can prevent the waste going down into the sewer, that’s a big part of the solution.

Q. FOG materials solidify and clog up the sewers?

A. That’s it. Dublin has proven a great example of dealing with this issue. Before 2008 they had up to 1000 blockages or fatbergs every year, and they were able to reduce it by over 90% over a few years, through a fats, oils and grease prevention programme. They appointed inspectors to go into restaurants under a new licensing system, so restaurants like this one here in UCD would have a licence under that programme, and they would get inspected maybe once or twice a year, depending on how busy the restaurant is.

Despite all the technologies we have, a simple thing like separating our waste is very effective. They would have also some equipment installed in the bigger restaurants, sometimes they are referred to as grease traps or grease recovery units, and again there’s a bit of a challenge in older buildings in the city centre where the buildings might be smaller and have protection orders on them and there might be limited space for them, so for example in the science building, this side of the science building, there’s a massive grease trap under the ground.

Whereas you go into the city centre where there are really old buildings, they might have a tiny room where they are working in the kitchen, they might not have the space for the proper, bigger grease trap, so they might have a mechanical system for grease recovery, skimming off fat as it floats on top of the water. The bigger the unit you can have the more residence time you have for the water which allows more of the grease to come up.

It’s also about training staff, it comes back to behaviour as well. To make sure that they are dry wiping off the plates into the food waste bin, rather than flushing it down the sink. It’s very simple behavioural stuff, combined with a bit of technology as well. Another challenge for restaurants is that you have many different cultures and languages operating in the restaurant and often a very high turnover of staff, so you have to have very simple instructions on the wall, often visual representations, of what to do, rather than depending on languages.

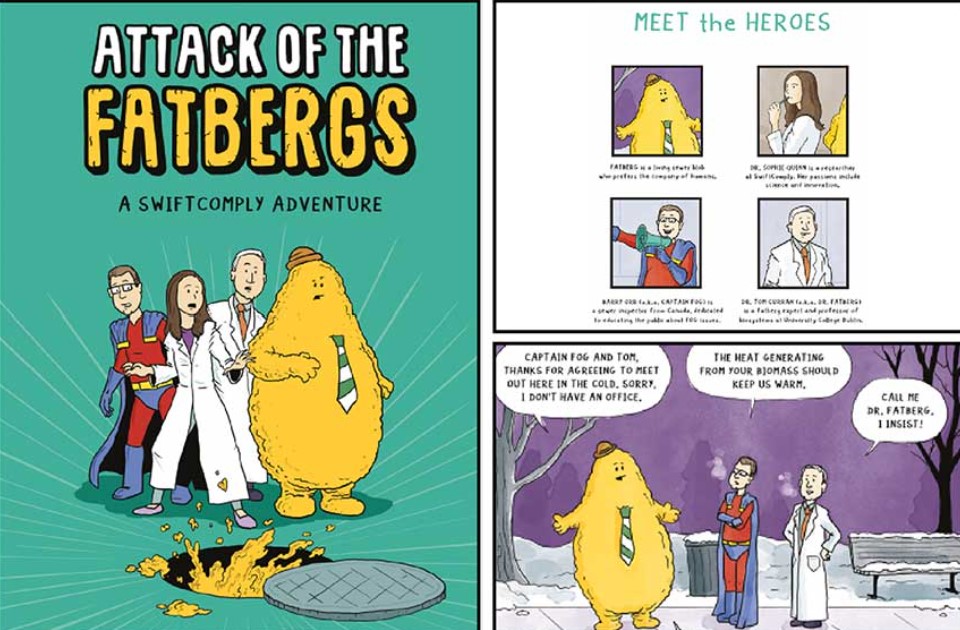

Q. These blockages or fatbergs became a big part of your Fulbright scholarship, how did that come about?

A. I had been working on fatbergs on an Irish Research Council project with a couple of researchers in collaboration with a former student, Michael O’Dwyer, he previously worked with Dublin City Council. He had set up a new company called SwiftComply, they developed a mobile app to make the FOG inspection process quicker. Now they’re in over 400 cities in America.

One of the things I learned from Fulbright was the communication of research. When I got the Fulbright scholarship my profile dramatically increased in terms of the media. There probably weren’t many experts who could say they were working on fatbergs. Also, people are very curious about fatbergs. It’s often a news item at the end of the news, ‘by the way we found a fatberg…’

Q. So the Fulbright really propelled your interest in public engagement and communications?

A. My profile really increased because that’s the nature of the Fulbright, everybody has a web profile as well as your UCD profile. Around that time in 2017 to 2018 there were some major fatberg blockages found in London, particularly in September 2017, and every few months I would get an interview request from a major media organisation, like the Guardian or USA Today, National Geographic, BBC World News, it was quite busy for a few years.

Q. I was fascinated to learn you’ve done stand-up comedy as well and featured as a character in a comic?

A. Yes. The whole thing has been a sequence of events, one thing led to another. When I did the IRC work with Michael O’Dwyer and SwiftComply on fatbergs, then I applied for the Fulbright and got that, and was doing a lot of media interviews. What I found with those was that despite all the technology and grease traps and sensors and all that, I remember what stuck with people was more simple.

I remember an interview I did with Sean Moncrieff on Newstalk, it was a live interview, and he asked me at the end what is your message for people? And I said, ‘just remember only flush the 3 Ps, paper, pee and poo’. And a couple of people said to me in the following days, I heard your interview and you were talking about the 3 Ps. They didn’t remember anything about the technology, they remembered the funny thing. So I learned that, the simple message is what is remembered.

A few months later there was a call out from the Bright Club, the comedy club for researchers, to see if anyone wanted to do stand-up comedy. I figured, from the interviews I’d done, people only remembered the funny things I’d said so I might as well try that. I’d had a few months to prepare for it and I’d been thinking what am I going to say, I had mixed feelings about doing the comedy and whether it was a good idea.

When I was preparing for it, my daughter was singing this song that was really annoying, a Taylor Swift song, Look What You Made Me Do, so I was wondering if I could use that. I made up a song, a parody of that Taylor Swift song, I think the punchline was, look what you make me do, please paper, pee and poo’.

That went up on YouTube and my industry collaborator Michael O’Dwyer said ‘I’ve seen your comedy, we’re thinking of promoting our company through a comic, how would you like to be a character?’ I had invented this character Dr Fatberg, trying to save the world. One of the Avengers movies was out at the time and I said I was like a fatberg avenger. I didn’t have to do anything, they actually created an image of me for it. I was very impressed by how it was there, there was even an easter egg in there for my benefit.

“My industry collaborator Michael O’Dwyer said, ‘I’ve seen your comedy, we’re thinking of promoting our company through a comic, how would you like to be a character?’ I had invented this character Dr Fatberg, trying to save the world. One of the Avengers movies was out at the time and I said I was like a fatberg avenger.”

Q. Was that the Taylor Swift reference?

A. Yes. In the comic, there’s a Taylor Swift poster behind me in the lab in UCD. So that was the funniest thing. Again it was one thing that people would remember. I mean I’m not a singer, I wasn’t really singing. It was definitely outside of my comfort zone but I said I’ll do this once and I’ll just go for it. I knew it was probably going to be on YouTube, but it was good fun.

Q. Your work often involves Life Cycle Analysis and footprint analysis – that’s very much about quantifying the cycle, the impact, the externalities of a product. Is that challenging in terms of accuracy, that quantification, why is it such an important first step?

A. It is a challenge. You need to get accurate information so you might have to do experiments to work out the impact. The more input you can have from reliable sources the better, to get the overall view on the life cycle assessment. Apart from the environmental assessment you also have to take into account the financial and social aspects as well. This connects back to behaviour of people. Is it acceptable to society, maybe a new approach to using byproducts?

One example that I think of is insect protein, and protein sources that might not sometimes be culturally acceptable in certain places. For example I was at an environmental conference a few years ago and I received free samples of snack foods incorporating some insect protein. As normal, I would bring back samples like these to my kids, but once they saw insect protein they wouldn’t even open the packaging. That just shows you the cultural challenge – if we bring in new changes for society, that might be technically feasible and good for the environment, it doesn’t actually mean it’s going to be acceptable.

In the AgroCycle project which looked at recycling and valorisation of agricultural waste, we engaged with producers of different types of byproducts from the food industry, because we need clean byproducts for the insects to grow on, vegetable materials for example, peelings. That is a challenge, even to get clean byproducts. That whole area is still ripe for disruption I think. I definitely think insect protein needs to be looked at, needs to be more acceptable.

Q. The agricultural sector in Ireland: what do you think are some of the key challenges?

A. I would go back again to the human behaviour side of things, I think there is sometimes a gap between the farming community and other groups in terms of sustainability. I think there’s a lot of potential there but we need to get people to understand each other’s perspective. I’m very interested in that aspect. We actually created two comics with the School of Archaeology, based at the Centre for Experimental Archaeology roundhouse.

We invented this girl character and her dog, Beo and Raja. The first one is called called Finding Beo. In the second one, Back to the Future with Beo and Raja, Beo and Raja are going to the roundhouse in UCD and they go back in time to what life was like in the time of St Brigid. People depended on nature to build their houses, they used hazel. They were looking at the hazel trees with a different view than what we see. They were thinking, that’s my next house. I need to look after that hazel tree so I can make my next house.

They built the houses in rotation as well, so they were thinking where is there next house coming from. One of the key things I learned was that the cow was an important part of culture at that time and It’s still ingrained in Irish society, the vast majority of farmers in Ireland have cattle whether it’s dairy cattle or beef, so we can’t forget about that cultural importance as well when you’re communicating with farmers about sustainability.

Q. What role does research informed public engagement have in these changes?

A. As I said at the beginning about BioCultúr, even in Ireland which is such a small country, there are different communities with different viewpoints. Like Leitrim and Wicklow having different perspectives on forestry. Even the language that people use, to refer to certain aspects of the countryside, can be very different. I had a very interesting discussion recently with a farmer he was telling me about names of fields, and even corners of fields, he had certain words, coming from old Irish words. As well as that, from a political point of view there’s an urban / rural divide and when people hear ministers possibly from an urban setting speaking to farmers in a particular way, they automatically think, they’re coming from an urban setting, they don’t understand.