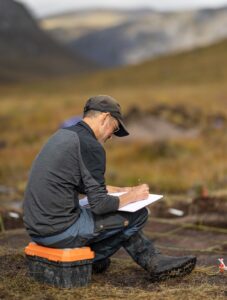

Photo: Excavations at Belderrig, Co. Mayo, Ireland

Hunter gatherers, Mesolithic Ireland, representations of the past, mountains and colonial legacies in archaeology with Prof. Graeme Warren, School of Archaeology

Q: Did you always want to be an archaeologist? What was your route into it and into what you do currently?

A: For my undergraduate degree I did ancient history and classical archaeology, which actually only had a very small amount of archaeology. Turns out that was the bit that I really, I really enjoyed. So when I came back for my master’s, it was archaeology that I focused on. Then I realised I was in exactly the right place, the right discipline and that it was the right thing to be doing. I studied at Sheffield in the mid-1990s, and went from that to PhD at Edinburgh in the late 90s, early 2000s. After that, I was very much that last generation of people who were able to get a job pretty quickly after PhDs without having to go through hundreds of postdoc positions. It was very lucky timing.

Q: Is that when you came to UCD? What did you like what about archaeology as opposed to history in general, as a discipline?

A: Archaeology is lots of different things to different people and there are many different ways of being an archaeologist. For me, it has a really nice mixture. There’s inherently an interesting task there, in trying to understand people’s lives from material remains. In particular with the stuff I do, which is relatively distant time and the material remains comparatively limited. You’re drawing on bits of philosophy, bits of social theory, bits of the sciences, bits of the physical sciences, all to try and create as best an understanding as you can of these past lives.

One thing that I really enjoy is archaeological fieldwork. You don’t have to like fieldwork to be an archaeologist but I happen to. It’s a privilege in many ways; that opportunity to be working outside. I’ve been lucky enough to work in some very nice places. Even when the places aren’t quite so nice, you’re not just walking through them, you’re spending a month, two months in that location, maybe over the course of years. You get to build up this understanding of different places. It can be revelatory, you don’t know what you’re going to find.

Q: What drew you to your particular interest in hunter gatherer archaeology, in this era of human history?

A: A couple of things. That picture just on the wall up there, my mum and dad found when they were clearing out. It’s drawn by me at seven years old writing at school about hunter gatherers – so there’s always been some interest! Part of it also was the master’s programme at Sheffield. I’d done no prehistoric archaeology so I was coming in on a conversion degree and playing catch up. We started with the Mesolithic, which is what I now do. One advantage of that topic is that there isn’t very much of it! I could actually become quite familiar with the material and then use that to for the later projects and stuff like that. Also, I was just back from travelling around for a year, and I had spent a long time in Tibet. I was really interested in mobile people and the ways in which they lived. It’s a simplification, but for much of the periods that I study, people were assumed to be quite mobile.

“in terms of the hunter gatherers, what’s interesting is the way they’re often imagined, particularly in popular culture, to tell us so much about who we’re supposed to be as humans. Hunter gathering is really important because of the role it plays in the public imagination.”

Q: Why do you think hunter gatherers are such an important focus for study? What are some of the challenges to understanding this aspect of human existence, what kinds of misconceptions are there in popular culture?

A: Hunter-gatherers in the prehistoric past can show us very different ways that humans have organised their societies and constructed their worlds: that’s the key thing. But in terms of the hunter gatherers, what’s interesting is the way they’re often imagined, particularly in popular culture, to tell us so much about who we’re supposed to be as humans. Hunter gathering is really important because of the role it plays in the public imagination. They are claimed by many to tell us about our evolved condition, our ancestral condition, if you like. Yet it’s not quite that straightforward!

In an Irish context, in spite of this interest, it’s quite interesting how they often don’t feature in accounts. For the first at least four thousand years of Ireland’s history, this island is only inhabited by hunter gatherers. in most of the textbooks, in introductory books to Ireland, it gets a page to a page and a half, maybe two pages, whereas later periods get much, much more attention. Quite often this period is relatively neglected.

“There’s lots of dynamism. There’s a history of hunter gatherers, they’re not just evolved and static and living in harmony with nature, they have their own really complex processes of change, which influence the landscape around them.”

Q: Is that because there isn’t very much evidence remaining?

A: I think partly because there’s not so much evidence, partly because that evidence isn’t as obvious and takes more work. I think it’s also about the assumptions that people make. To stay with the Irish example, the assumption might be that for those four thousand years, all people did was hunt and gather. You know, they were hunters and gatherers, they ate wild food, they were mobile. Whereas we recognise now that there’s lots of change. There’s lots of dynamism. There’s a history of hunter gatherers, they’re not just evolved and static and living in harmony with nature, they have their own really complex processes of change, which influence the landscape around them. It’s that side of things that we’re now beginning to understand much more, even in an Irish context. There is an incredible amount of diversity within the group of people that Western thought labels as hunter-gatherers.

Q: I didn’t send you this question but I suppose I’m wondering then, how much sense does it make as a overarching category? Is it a good idea to categorise people based primarily on that aspect of their lives?

A: Well, ish, yes! You’re talking somebody who runs an MSc in Hunter-Gatherer Archaeology! It can be useful but it depends on the questions. Most people define hunter gatherers as a series of overlapping ideas – that they eat wild food and plants, they don’t have any domesticates. They are highly mobile. They may be only live in small groups and are very egalitarian. Quite often those things do overlap, but not always.

There are people who eat wild food who are mobile, who are egalitarian. But there are also people who eat wild food who live in permanent villages have hereditary slaves and chieftains, and there are people who practice swidden horticulture, so have domesticated resources, who are egalitarian and move around a lot. So for some of those questions, it might be interesting to talk about hunter gatherers, for other ones, what you might want to talk about are class relations, or the nature of mobility.

Q: What about time periods? Is there synchronicity of this kind of existence across Europe, Ireland or around the world for instance? Or is it very varied?

A: Well, hunter gatherers continue into the present. One of the problems that happened a lot, particularly during the 19th and early 20th century, is people would take hunter gatherers in the present and say “that’s how we used to live in the past”. Tasmanians for a long time were considered by Europeans to be the most primitive people they had encountered. They were assumed to be living in the same way as people did in the earliest stages of European prehistory. The strange thing is people are doing it again in recent scholarship. They’re making those same comparisons.

There’s been loads of work trying to highlight some of the ways this works. There’s lots of debate around the Kalahari San, or the Bushmen. There’s problems with both of those terms. They’re always held up as the exemplar of the human past. There’s really good research carried out there. But at the same time, particularly in popular representations, it’s quite problematic. It’s not uncommon to see a newspaper report about research about our past hunter gatherer selves and they’ll just stick a picture of the San on it, even when it doesn’t have anything to do with the story.

“Undoubtedly, in popular discourse, there are a lot of very simplistic ideas about hunter gatherers. They’re very romanticised, there’s a nostalgia for something which we somehow lost. We suggested in the paper that hunter gatherers are held up to be both the antithesis and the antidote to modernity.”

Q: It seems like hunter gatherers are often romanticised or simplified, particularly in terms of diet and relationship to nature? Do you have any views on this from your own insights?

A: A few! We wrote a paper recently about the way in which hunter gatherers are represented in popular discourse. We looked at discourses around physical health, mental health, prepping and survival skills. Undoubtedly, in popular discourse, there are a lot of very simplistic ideas about hunter gatherers. They’re very romanticised, there’s a nostalgia for something which we somehow lost. We suggested in the paper that hunter gatherers are held up to be both the antithesis and the antidote to modernity. This is usually in terms of the idea that everything went wrong for humanity with the invention of farming – that it was that change that put us on the path towards accumulating more and more things, living in bigger groups and increasing amounts of social inequality. Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything is a reaction to that to that narrative.

Nowadays, people are being encouraged to try out hunter gatherer things, like ‘caveman therapy’ for men. Something like that is promoting men’s mental health and that’s a really good thing. People saying that it’s good to get outside and practice traditional craft. Again, it is really good to get outside and do that. But in all of these, it’s actually the figure of the hunter gatherer they’re stressing, not a peasant agriculturalist, not a pastoralist. It’s the idea of the hunter gatherer that gets emphasised, because it is believed to represent our true evolved selves.

Quite often the actual evidential basis for some of these claims of what our hunter gatherer ancestors did is quite limited. For instance, the paleo diet often talks about not having much carbs and having large amounts of protein, when actually the more we’re developing analytical techniques and look at things like tooth calculus, it’s showing that people ate much more starch than we thought. The evidential basis can be quite problematic.

Q: What about hunter gatherers in Ireland? Do they follow a fairly similar path to the rest of Europe?

A: The Irish Mesolithic has always been treated a little bit different than other parts of Europe. There’s a whole variety of reasons for that, some of which is tied up with the island identity of Ireland, some of which is tied up with issues around nationalism, some of which is tied up around colonial ideas about islands. One of the things people have often talked about is the types of stone tools that people make in Ireland. While it starts the same as the rest of Europe, it becomes quite distinctive. The only other place that does similar things is the Isle of Man.

That’s often been held up as being a story of Irish difference, overall, and there are aspects of differences. But there’s also lots in common with in Britain, and with France, as well. The development of the distinctive Irish stone tool technologies is a part of a trend, which is also going on through Britain at the time, towards increased regionalisation. The reasons for that change in stone tools have been discussed a lot. Is it because there was a limited range of large mammals in Ireland? Because Ireland was an island from very early on, some of the large mammals that got into Britain didn’t get across to here. Others have suggested it is to do with changing social organisation and mobility.

Q: What was the difference in the tools?

A: The first types of Mesolithic stone tool technology in Ireland are things called microliths. They are small, like a centimetre or two, carefully shaped. You might put seven or eight of them in a row to make a blade of a knife, or three or four of them to make a barb for an arrowhead. However, these stop being manufactured in Ireland. They start focusing much more on making larger leaf shaped or elongated blades or flakes, maybe five or ten centimetres long.

It does at least seem plausible that the absence of things like red deer or auroch, a species of wild cattle, from Ireland would have made a difference to the sorts of technologies that people used. The change happens roughly 1000 to 1500 years after people first settled here, so it takes some time. There are some dates to resolve. But to me it would be unsurprising if a general trend in northwest Europe to regionalisation became more marked in an area where that region has a very distinctive ecology.

Q: Tell us about your interest in mountains and your work with the Mountain Research Group which was initially funded as an Earth Institute Strategic Priority project

A: The Mountain Research Group is coordinated by myself, Sam Kelley (Earth Sciences), and Christine Bonnin (Geography). it’s a nice extension of some of the things I said about archaeology earlier on being interdisciplinary. Sam and I have worked together on projects, Christine and I have worked together on projects. Mountains are almost inherently interdisciplinary. To understand them you really have to use lots of different perspectives. For example, we go out into mountain landscapes in Scotland trying to find hunter gatherer sites, but when you walk into that landscape, you’re walking into a landscape has changed considerably since the time since hunter gatherers were there. It can be 10,000 years since they were there. Sediment has come down rivers and buried sites, other areas have eroded. If you were to spend time looking for sites without first of all assessing the age of the landforms, you could be wasting huge amounts of time.

Q: Are there ways of working out which sites are more likely to be relevant?

A: Sometimes I can do that in the field. But you might need someone who’s a specialist in geomorphology to come out and say, okay, yeah, that’s going to be that type of thing, that’s going to be that type of age. Those changes in the landscape also mean that there were different opportunities there. For hunter gatherers in the in the past, they were not living in the landscape that we see today. So again, you need to work with other people to see that. One of our sites in in Scotland, Chest of Dee, is at the moment located by some quite distinctive waterfalls. It would be really easy to imagine that’s the reason that people settled there. Actually however, when the hunter gatherers were first settled there, there wasn’t a waterfall. The river was running on the other side of the valley. You have to understand that landscape change. You have to work through that.

“We go out into mountain landscapes in Scotland trying to find hunter gatherer sites, but when you walk into that landscape, you’re walking into a landscape has changed considerably since the time since hunter gatherers were there. It can be 10,000 years since they were there.”

Q: How does what you work on connect to environmental and sustainability challenges today?

A: In lots of different ways. The first point to make is the most of my work covers the period at the end of the last ice age and the start of the Holocene. In Ireland and Scotland, you’re looking at the period from about 12500 BC down to about 4000 BC. That’s a period of enormous climate and environmental change. We see the retreat of the ice sheets at the last glacial maximum, the warm period of the interstadial, then a cold snap again, where ice advances from the uplands, and then the warming and establishment of a whole new deciduous woodland environment. People’s lives were interwoven with those with those changes. Quite often our work is trying to find out about the what the humans were doing as well as out what the landscape was doing.

In part our work is generating more data about past climate change, which obviously we can use to help understand what’s going on today. There are some who think that we might find the solutions in the past to current climate challenges. I don’t particularly think that how hunter gatherers might have adapted to climate change eight thousand years ago is going to fix how we’re going to adapt to climate change now. I think that that’s quite an instrumental approach. But you can certainly use it to be thinking about scales of change, how it’s affected these particular landscapes.

Initially in the Cairngorms some people had found some stone tools on a footpath on Mar Lodge Estate, which is owned by the National Trust Scotland. Mar Lodge as a National Trust site was being managed for both natural and cultural heritage. They were having problems because global climate change has led to increasing river temperatures and the freshwater pearl mussel was in decline significantly. So in order to preserve the habitat for the freshwater mussel, which was a protected species, National Trusts had to plant riparian woodland for shade, which the National Trust archaeologist Shannon Fraser was really concerned about, because all of the places where people had found flint tools were right by the rivers and planting trees might impact the archaeological evidence.

That original funding was from the National Trust to excavate where we’d found these flints. The aim was to see was this a real site or was it just somewhere where some material had been washed up? Could we work out ways of predicting sites and could the horribly complicated job of managing the entire estate be better informed archaeologically? It’s been a real education in thinking about some of those things. Mar Lodge have a five hundred year woodland management plan. That’s an interesting concept!

“The funny thing about Glendalough is that you’d imagine that we know all there is to know! But that’s not the case. We’re digging quite close to the main monastic complex and we found the original enclosure ditch of the monastery. No one knew it was there before our excavation. It was eight metres wide and two metres deep.”

Q: Tell us about the work you do in Glendalough and the role of archaeology in heritage and community

A: The work in Glendalough is myself and my colleague Conor McDermott, with a host of others. We’ve been working in that valley since 2009. It initially was our teaching project. There’s a lot of really obvious archaeology on the ground, you can see it and there’s a lot of stuff underground, and lots of questions about the history of that valley. But we realised quite quickly working there that you have this remarkable opportunity to engage the public and work with the public. We have photos of us in the early years in an excavation trench with a fence around it, eight or nine students diligently working away in the middle of it, with that whole fence surrounded by members of the public, staring over at us.

We develop different strategies for it. We formed what’s called the Glendalough Heritage Forum, which has local community and representatives of state agencies. That was trying to get people to work together to promote chances for collaboration and cooperation. Since 2016 we’ve been running a community excavation, so every summer, two weeks, we take volunteers from anywhere. Some are very, very local, and some travel to come there, and they work with us on site. That’s been brilliant. We’ve got people who’ve returned year after year and a visitor book full of people saying, this was the best day of my life.

Q: Is there still much of Glendalough to be excavated?

A: The funny thing about Glendalough is that you’d imagine that we know all there is to know! But that’s not the case. We’re digging quite close to the main monastic complex and we found the original enclosure ditch of the monastery. No one knew it was there before our excavation. It was eight metres wide and two metres deep. We also found a 12th century water mill with stone lined mill channels running hundreds of metres. We’ve found enormous things.

As well as structures, some artefacts tell us really important stories about connections to different places. We found a little jet cross. Jet fossilised wood, about a centimetre maximum size. It has a dot and circle motif inlaid in it. There’s only about thirty of those found in Europe. They’re found in the north of England, they were probably manufactured near Whitby. You have five or six of them in Ireland. You have one in Trondheim, and you have one in Greenland. It’s this 12th century Norse world. We’re up there high in the Wicklow Mountains in this supposedly isolated monastery and you’ve got artefacts linking you to Greenland.

“We found a little jet cross.. […] There’s only about thirty of those found in Europe. They’re found in the north of England, they were probably manufactured near Whitby. You have five or six of them in Ireland. You have one in Trondheim, and you have one in Greenland. It’s this 12th century Norse world.”

Q: You’ve written about colonial legacies in terms of archaeology. Can you tell us a bit about what kind of these legacies might persist in terms of how human development is understood?

A: I was chatting to the master’s students about this recently. I had just given a first year lecture in which I talked about the Mesolithic period being about prehistoric hunter gatherers. That’s the classic definition. But every single one of those concepts is deeply entangled with colonialism. The idea of the Mesolithic, the idea that there’s such a thing as hunter gatherers, even the idea of prehistory itself is a bound up in that, and many of those associations are really quite problematic. In terms of hunter gatherers, people in the present were held up as being evidence of our past. That that they were primitive, they were unchanged, less civilised, they hadn’t progressed was used to justify genocide and land grab. There are some parts of the world where people are very resistant to using that kind of terminology as a consequence of that.

The Mesolithic is a colonial concept, it arose to solve a particular stratigraphic problem in the northwest of Europe, and was exported through the dominance of English language through English colonial structures. The Mesolithic ends up being used by the Survey of India very rapidly in the 19th century. The Survey of India was a colonial tool in order to work out what they could extract from India so the success of that concept is bound with that colonial history. There’s also discussion around prehistory as well in the same way. Some of the fundamental concepts that we use have their origins in colonialism and not always just in a neutral kind of kind of way

Hunter-Gatherer Ireland: Making Connections in an Island World by Graeme Warren

(2022, Oxbow Books)

You have to find alternatives to it. I’ve published a book called Hunter Gatherer Ireland. I did that having reflected on whether I could justify the use of the term and using it as a way of problematising the term itself. It has a certain impact in an English-speaking context. It carries certain resonance for people, you can hook people with it. But then I think you have to try and break it down and highlight lots of those problems.